Redistricting Rundown: Virginia

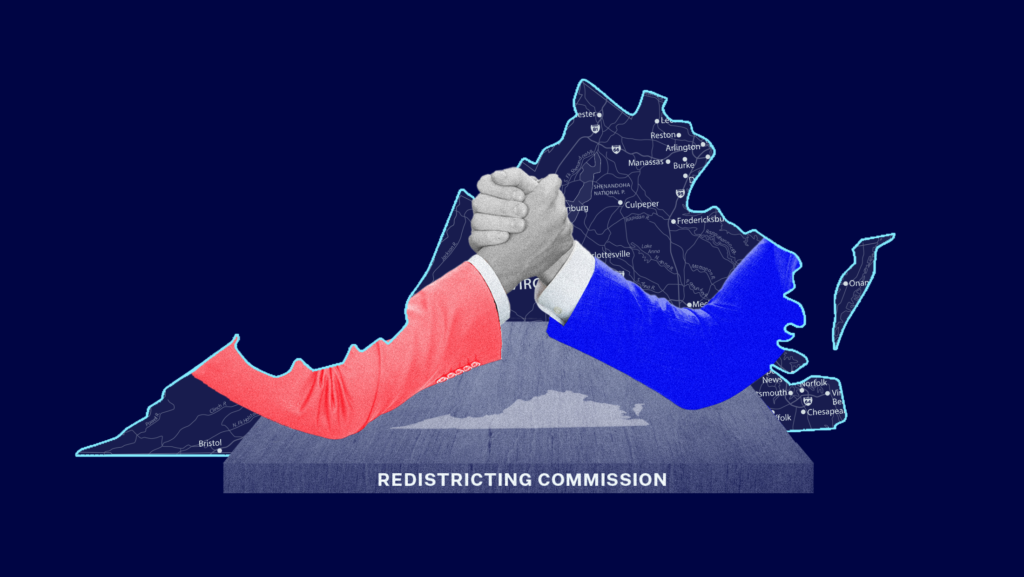

While redistricting is always bound to provoke controversy, in no state has it proven quite as contentious as Virginia so far this cycle. Last year, voters approved an amendment creating a new commission to handle redistricting. Reformers hoped the amendment would ensure Virginia has fair political maps, after a decade in which districts were repeatedly overturned for violating federal law and the U.S. Constitution. But rather than draw fair maps, the commission failed to draw any maps at all. In this week’s Redistricting Rundown, we’re taking a look at what happened in Virginia.

After a turbulent decade, Virginians approved the creation of a bipartisan commission to handle redistricting.

In the November 2020 elections, Virginians approved Question 1, an amendment to the Virginia Constitution designed to reform how the state redraws congressional and legislative districts. The amendment was the culmination of a major push to reform redistricting in the state after a decade of controversy. The congressional districts adopted by the Virginia General Assembly in 2011 were overturned in 2014 by a federal court for packing Black voters into the state’s 3rd District. In 2018, several of the state’s legislative districts were also overturned for being unconstitutional racial gerrymanders. On top of these legal challenges, Virginia Republicans tried repeatedly to redraw legislative districts in 2014 and 2015, with Gov. Terry McAuliffe (D) vetoing each attempt.

The amendment shifted redistricting responsibility from the General Assembly to a 16-member commission — eight citizens and four legislators from each house, equally divided between the two major parties. Any redistricting plan needs the support of at least six of the citizen commissioners and six of the legislative commissioners. Additionally, the plans for each of the houses of the General Assembly have to earn support from at least three of the four commissioners from that house. Per the Virginia Constitution, the commission is required to draw maps that are contiguous and compact. The General Assembly also passed additional statutory criteria for the commission to follow when map-drawing, including a state-level Voting Rights Act, protections for communities of interest and a prohibition on partisan gerrymandering when considering a map on a statewide basis.

Plans approved by the commission are presented to the General Assembly, which must either approve or reject the plan without changes. If the General Assembly rejects any of the commission’s proposals, the commission can draw a second version for consideration. If the second proposal is also rejected, or if the commission fails to submit a plan, new districts are drawn instead by the Supreme Court of Virginia. The Court will hire two outside experts — one selected by Republicans and one selected by Democrats. The experts will then prepare maps for the judges to consider.

While the amendment was supported by a broad coalition of politicians and political organizations, including the League of Women Voters, the ACLU of Virginia, Sen. Tim Kaine (D) and former Virginia Gov. George Allen (R), the amendment was criticized by some members of the Democratic Party. Several members of the Virginia Legislative Black Caucus opposed the amendment for not guaranteeing sufficient protections for minority voters. The Virginia Democratic Party urged voters to reject the amendment, raising concerns that it gives Republicans and conservative judges too much power to draw maps that don’t reflect the state’s political preferences. Many Democrats also argued that a truly independent, rather than bipartisan, commission would be a better reform. Despite this, the amendment passed easily, winning in every single county and independent city in Virginia except for Arlington.

In the face of partisan disagreements, Virginia’s commission completely failed to draw new districts.

The Virginia Redistricting Commission got off to an inauspicious start when delays in the census meant it wouldn’t be able to draw new General Assembly maps in time for the 2021 election next week. The process then quickly became marred by partisan disagreements. The Commission couldn’t agree on hiring a single outside counsel and instead voted on June 7 to hire both Democratic- and Republican-affiliated lawyers. Similarly, the commission also deadlocked on a proposal to hire nonpartisan University of Richmond data specialists to assist the commission with map-drawing. It ended up hiring separate teams of Republican and Democratic consultants.

The Commission first focused on crafting new maps for the House of Delegates and Senate. However, it struggled to find a way to merge the separate proposals of the Democratic and Republican consultants ahead of an Oct. 10 deadline. Race was also a sticking point, as the Democratic and Republican lawyers gave conflicting advice and the commissioners disagreed on the creation of “opportunity districts” — districts where minorities constitute 40 to 50% of the voting-age population. These struggles culminated in a dramatic Oct. 8 meeting where Republican commissioners rejected a compromise proposal to begin final plans from a Republican-drawn House of Delegates map and a Democratic-drawn Senate map. Several frustrated Democratic members walked out in response, depriving the commission of a quorum and leaving it unable to meet the deadline.

Rather than seek a 14-day extension, the Commission turned instead to working on the state’s 11 congressional districts, punting legislative map-drawing to the state Supreme Court. But the Commission was no more successful with drawing a congressional map, reaching another partisan stalemate on Oct. 20 ahead of an Oct. 25 deadline. The Democrats proposed a plan with five Democratic-leaning districts, four Republican-leaning districts and two competitive districts. Republicans countered with a map with five Democratic- and Republican-leaning districts and just one competitive district. Both proposals failed on party-line votes. Democrats rejected the Republican proposal for being out of line with the state’s voting patterns, as Republicans currently only hold four congressional seats and have not won a statewide election since 2009.

While the Commission could theoretically still return and approve a congressional map within a 14-day extension period that ends Nov. 8, it is likely the state Supreme Court will have to step in and take over congressional redistricting as well.

Virginia’s redistricting debacle highlights the potential pitfalls of reform.

Rather than create fair maps for Virginians, the state’s new commission utterly failed at redistricting, leaving Virginia’s political future in the hands of the conservative-leaning state Supreme Court that is unelected by voters. The case of Virginia shows that merely adopting a redistricting commission doesn’t guarantee a fair outcome. In the wake of the commission’s implosion, commentators have identified two fatal flaws: being bipartisan rather than independent and lacking a tie-breaking mechanism in case of a stalemate. In the current political climate, where partisan considerations dominate practically every aspect of our politics, compromise between the two parties is increasingly unlikely. Not all commissions are created equally, and in some ways, Virginia’s commission was doomed to fail from the very beginning.