Redistricting 101: Why Maps Go to Court

When you hear the word “redistricting,” your mind might jump right to lawsuits. That’s because redistricting can be a fraught process (rife with many big words) often leveraged by Republicans to pass unfair and unconstitutional maps, and some of the best protection voters have against disenfranchisement is through the courts. Learn when to expect litigation over this decade’s maps and why it matters in today’s Explainer.

When does redistricting happen?

The timing of redistricting is intertwined with the U.S. census. Our Constitution requires that we count all residents in the country once every 10 years, and Congress delegated the task of counting to the U.S. Census Bureau. The number of residents in each state determines the number and size of its legislative and congressional districts, which then determine the number of representatives each state has. This year, due to delays in gathering data caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Census Bureau delivered the population counts to President Joe Biden on April 26. It will deliver raw data to the states by Aug. 16, 2021 and final redistricting data to all states and the public by Sept. 30, 2021. Once the states have the population counts, they can begin the process of drawing district maps and drafting apportionment legislation to turn those maps into districts.

The timeline to actually pass a new map differs by state. For example, the Kansas Constitution requires the state to conduct reapportionment in the legislative session two years after the census; therefore, the Kansas Legislature will not draw the next map until 2022. But other states, like Pennsylvania, have no set timeline and are preparing to draw new legislative maps upon the release of census data. Additionally, some states have different processes and timelines for drawing state legislative districts than for drawing congressional districts. And, while some states will leave map drawing exclusively to state legislatures, other states, like Arizona, employ an independent commission to draw congressional and legislative district maps.

For states with no set timeline for redistricting, it’s helpful to look at deadlines related to an upcoming election. For example, candidate filing dates — the deadline by which candidates who wish to run for office in an upcoming election must file paperwork — and state primary elections are good benchmarks for when new district maps will be drawn. As we approach the Census Bureau’s deadline to release the data, we’ll know more details about when states will draw new maps.

Why are there redistricting lawsuits?

State legislators working to adopt new district maps face three common scenarios:

- The state House and Senate agree on a map (called the “apportionment bill”), and the governor signs it into law.

- The state House and Senate agree on a map, but the governor vetoes it.

- The state House and Senate cannot agree on a map, making an impasse likely.

Each of these scenarios could lead to litigation: Parties may sue under the first scenario if the bill that the governor signed is unconstitutionally gerrymandered or violates the Voting Rights Act by failing to adhere to the requirement of one person, one vote. Parties may also sue under the second and third scenarios to ensure an accurate map is drawn in time for an upcoming election.

Why do lawsuits matter?

Challenging unlawful maps in court is important to guarantee districts are fair and representative of the people they encompass. For example, in 2010, the GOP-led Pennsylvania legislature redrew its map so that 13 of the 18 districts were solid Republican districts, despite the statewide vote evenly splitting 50/50 between parties in presidential, senatorial and gubernatorial elections. The map was so politically gerrymandered that almost half of the Commonwealth’s counties were split between at least two different congressional districts.

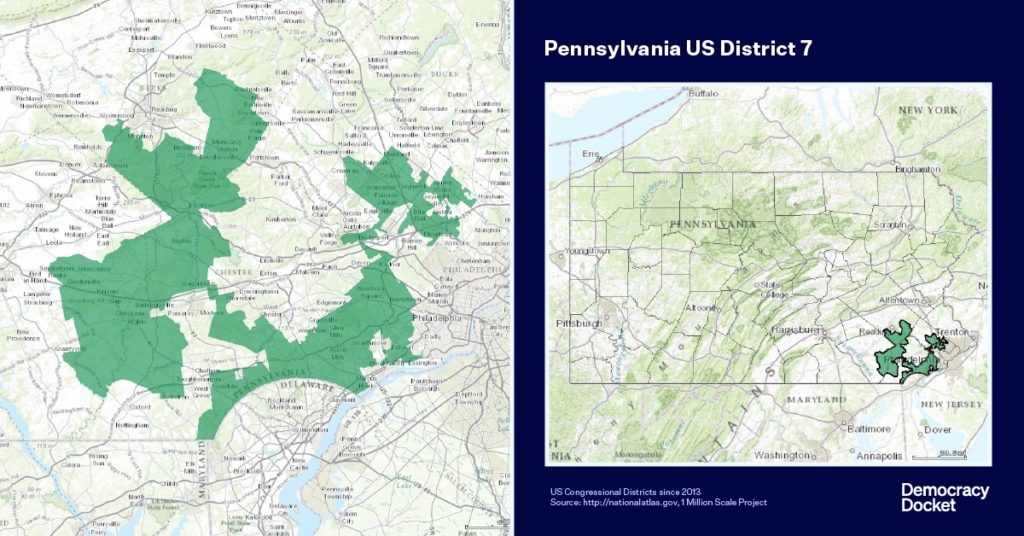

Pennsylvania’s 7th Congressional District, one of the most gerrymandered districts in the country at the time, was barely contiguous — meaning different parts of the district barely connected with others. Some points of the district were only connected by a single building — one connecting point was a medical facility, and another was a restaurant, Creed’s Seafood & Steaks. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court found the map deprived voters of their right to a free and fair election guaranteed by the Pennsylvania Constitution, and now Pennsylvania’s congressional map is an even split of nine Democrat and nine Republican districts.

After the 2010 census, Virginia passed congressional and legislative maps that were racially gerrymandered because they purposely packed African American voters into districts to limit their voting power. Courts found these maps to be unconstitutional because race was a predominant factor in their drawing, and they were struck down. Under new maps, Virginia’s U.S. House delegation flipped from majority Republican to majority Democrat, and Democrats grew in power in the state Legislature.

When elections are conducted based on newly drawn maps, the representative makeup often shifts. In many states, these initial maps might be unconstitutional, denying thousands of voters a fair chance to have their voices heard or their representatives of choice elected. In these cases, litigation plays a huge role in safeguarding our most cherished democratic ideal of free and fair elections.

Stay tuned for more information and resources about redistricting as we wait for the full release of 2020 census data. If you haven’t already checked out our Redistricting 101: How We Got Here Explainer, you can find it here.