Presidents’ Day: From the White House to the Ballot Box

Without a doubt, the biggest legislative achievements throughout history were the results of years of activism and movement building, rather than the accomplishment of a single leader in the White House. However, if the president throws their weight behind a movement — or shirks responsibility — it makes a difference.

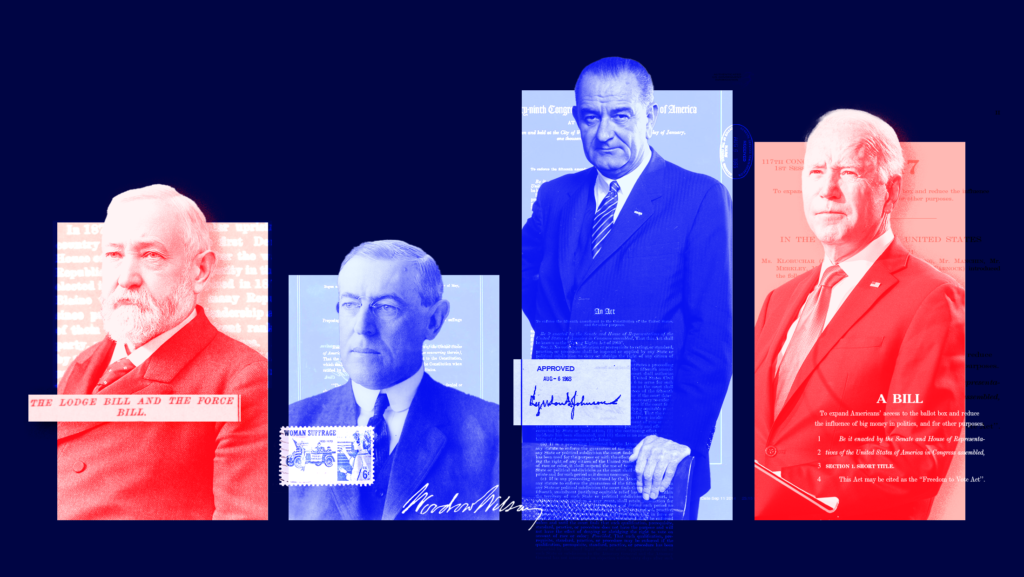

As we celebrate Presidents’ Day 2022, we’re taking a look at four key inflection points for voting rights when the head of state either stepped up or failed to meet the moment, whether within their control or not.

President Benjamin Harrison stood by as the Federal Elections Bill of 1890 was defeated.

The post-Civil War constitutional amendments ensured that the right to vote was not restricted due to race. Even though this was now enshrined in law, there was a stark difference between rights on paper and in practice.

By 1890, 13 years after the effective end to Reconstruction, southern states were starting to pass laws specifically devised to prevent Black men from exercising their newly granted right to vote. In light of this, Henry Cabot Lodge, a Republican congressman from Massachusetts, championed a federal elections bill (known as the Lodge Bill) that would have provided mechanisms for federal oversight of elections, focused on enforcing the 15th Amendment.

After passing the U.S. House of Representatives, the Lodge Bill failed in the U.S. Senate. The bill was ultimately filibustered by southern Democrats, but lackluster efforts by Republicans solidified its defeat. President Harrison eventually endorsed the bill, but he stood idly by as his party chose to prioritize other issues instead.

The former governor of Louisiana, William Pitt Kellogg, scathingly critiqued Harrison for his too little, too late embrace of the Lodge Bill. “Selfish interest invoked action,” said Kellogg in asserting that Harrison only supported the bill when it became politically expedient to. Kellogg accused Harrison of abandoning the rights of Black voters for the sake of “building up a white Republican Party in the South.”

New York Times columnist Charles Blow recently wrote about the Lodge Bill and its parallels to today: “The racists won, and Black voters lost because the party they supported and considered their friends did not fully mobilize to defend them from the party that sought to oppress them.” Instead of committing to equal rights, Harrison wavered and sat by as federal action to stop Jim Crow tactics in its tracks was punted another 70 years down the line.

President Woodrow Wilson long opposed federal action on women’s suffrage, but eventually endorsed the 19th Amendment.

After decades of political organizing, women’s suffrage finally gained traction in the 1910s, but only on a state-by-state basis. For years, President Wilson publicly opposed any federal efforts for women’s suffrage. Wilson, with his misogynistic (and racially charged) views, had every intention to uphold the status quo.

A shift came in 1918 when Wilson finally aligned himself with the women’s rights movement once it became politically convenient to do so. “Both of our great national parties are pledged, to equality of suffrage for the women of the country,” Wilson declared in an address in front of the Senate in September 1918. “Neither party therefore, it seems to me, can justify hesitation as to the method of obtaining it, can rightfully hesitate to substitute federal initiative for state initiative.” Wilson tied the passage of the proposed amendment that lay before the Senate to the success of the United States’ military endeavors abroad.

The constitutional amendment would fail one more time in the Senate before passing the following year. And in 1920, the 19th Amendment was ratified, officially granting women the right to vote. Despite this achievement, it was white women who solely benefited from this extended suffrage, at the expense and exclusion of women of color.

While Wilson’s endorsement did not come about because of a radical change in personal beliefs, the amendment ultimately prevailed during his presidency, proving Wilson a reluctant ally, but an ally nonetheless.

After years of civil rights activism, President Lyndon Johnson’s unwavering support pushed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 over the edge.

The Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965 stands out as a watershed moment in the history of voting rights in the U.S. The VRA banned the use of literacy tests, created federal “preclearance” requirements for states with a history of suppressing Black voters and more. The impact was immediate: over 250,000 new Black voters registered by the end of 1965 alone.

Despite years of activism and growing momentum in the civil rights movement, successful passage of such expansive federal legislation was no guarantee — until President Johnson made his position unequivocally clear.

On March 15, 1965, Johnson convened a joint session of Congress, a rare occasion typically reserved for highly ceremonial occasions like the counting of electoral votes or State of the Union address. Johnson’s speech was televised and watched by over 70 million Americans. He began by describing events that took place just eight day prior: the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama that became known as Bloody Sunday.

Johnson explained how there is no cause for pride for what happened in Selma nor in the continued denial of Americans’ rights. “Experience has clearly shown that the existing process of law cannot overcome systematic and ingenious discrimination,” Johnson argued, instead making the case for comprehensive federal legislation. “No law that we now have on the books—and I have helped to put three of them there—can ensure the right to vote when local officials are determined to deny it.”

Two days later, the very legislation that Johnson described was introduced in Congress as the VRA. It passed a few months later, and was signed into law by Johnson on Aug. 6, 1965.

While Johnson was initially concerned about timing (less than a year after the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 and amidst a push for new Medicare legislation), after being galvanized by Bloody Sunday, he didn’t waver in his stance. After all, Johnson made clear that we would accept “no delay, no hesitation and no compromise.”

President Joe Biden pushed hard for voting rights legislation. But Senate opposition derailed the effort.

Just last month, the country saw another opening for momentous change: passing the Freedom to Vote Act and John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. This legislation would have combated Republican voter suppression and election subversion efforts led by former President Donald Trump.

In a rallying call to lawmakers, President Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris traveled to Georgia to speak on the importance of protecting the right to vote. “I’ve been having these quiet conversations with the members of Congress for the last two months,” Biden said, in explaining his position on the issue. “I’m tired of being quiet!”

In a stark contrast to his predecessor, Biden stood up for voting rights and used the full force of his bully pulpit to do so. Even as a self-proclaimed institutionalist who spent decades in the Senate, Biden explicitly endorsed changing the filibuster rules to ensure legislation was passed: “To protect our democracy, I support changing the Senate rules, whichever way they need to be changed, to prevent a minority of senators from blocking action on voting rights.”

Despite Biden’s efforts and the momentum he helped build, the legislation could not overcome Senate obstruction — all 50 Republicans opposed the voting rights bills. They were joined by two Democrats who placed their loyalty to arcane Senate rules above our democracy, extinguishing any hope for federal legislation at this time.

Even if there are factors outside of the president’s control, history shows how the legacy of an administration is shaped by the successes and failures around them. Some presidents wavered and allowed crucial voting rights priorities to pass them by. Others embraced change, but only because it was politically advantageous. Most recently, we saw a president who pushed for action but was unable to overcome other institutional roadblocks.

Looking forward, it’s clear: we should expect our president to utilize the full force of that office to be bold and protect democracy.