New Report Sheds Light on Hand Counting Ballots Ahead of 2024

A new paper, exclusively obtained by Democracy Docket, details the increasing prevalence of hand counting, analyzes the risks of the method when done wrong and highlights the ideal ways electronic and hand counting can work together to safeguard and modernize U.S. elections. Published by Verified Voting, a nonpartisan, nongovernmental organization that researches the intersection of technology and election administration, the report comes at an integral moment for the future of American democracy.

Following the 2020 presidential election, when former President Donald Trump and Republicans nationwide cast unfounded doubt on the integrity of electronic voting machines, there has been a surge in calls for hand counting as a replacement for the machines. The demands have continued into 2023 — at least eight states have introduced bills that would ban the use of vote counting machines.

Deep red counties have been hotspots for controversy over hand counting.

Republican efforts to hand count extend beyond haphazard legislative proposals; Conservative counties across three different states have attempted to hand count their election results, despite pushback from statewide officials.

In 2022, Cochise County, Arizona, a small Republican-controlled county, attempted multiple misguided hand counts. After originally planning to conduct a hand count audit of all ballots cast in the 2022 midterm elections, the county’s supervisors voted instead to exclude early ballots from the hand count audit and limit the hand count to only a few races.

In its report, Verified Voting makes a clear distinction between hand counting all ballots and hand counting in order to confirm election results in the form of post-election audits. Post-election audits feature transparent hand counts that take place days after the election, involve batches of ballots and are provided ample time to complete whereas plans to hand count all ballots are extremely time consuming and costly.

Arizona’s Republican attorney general at the time, Mark Brnovich, issued a non-binding advisory opinion in October 2022 that greenlit Cochise County’s plans to hand count, writing that the county “has discretion to perform an expanded hand count audit of all ballots cast in person…along with 100% of early ballots cast” in five contested statewide and federal races on the 2022 ballot.

After a lawsuit was filed to stop the county from hand counting, a judge ruled a day before the election that Cochise County cannot move forward with its plans. Even though the supervisors appealed that decision and the lawsuit continued for months after, the county ultimately did not hand count the 2022 midterm elections

This past October, an Arizona appellate court upheld the lower court ruling that blocked Cochise County from hand counting, and further barred the county’s future plans to hand count.

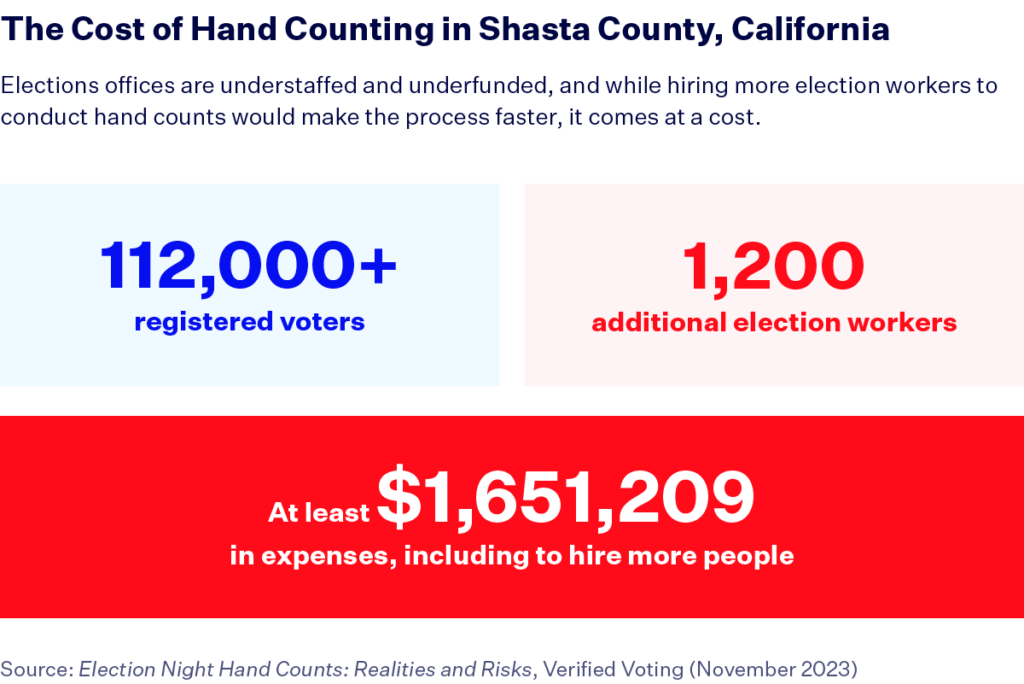

Home to more than 112,000 registered voters, Shasta County, California — a deep red county in the northern part of the state — had also developed a dangerous plan to hand count all of its ballots, a move estimated to require 1,200 additional workers and cost over $1.6 million. After canceling its contract with Dominion Voting Systems in January of this year, the Shasta County Board of Supervisors voted to not replace the machines with new ones, but rather to hand count all ballots. The Democratic attorney general of California had warned the county against hand counting.

Largely in response to Shasta County, the California Assembly passed legislation in June that effectively barred the county from carrying out its hand counting plan in the November 2023 elections. Yet Republicans on the board continued to insist for months they would carry out the plan anyway, with the board’s Republican chair claiming the “supervisors were still committed to implementing a hand count regardless of what the law says.”

Ultimately, after warnings from the Secretary of State Shirley Weber (D) and multiple advocacy groups, the county abandoned its plans to hand count just days before the elections earlier this month.

On the contrary, after a wave of legal and legislative back and forths, the Nevada Supreme Court allowed Nye County to continue counting all ballots that had previously been tabulated by voting machines. While the plan was allowed to go through in ways Shasta and Cochise were not, the results were deeply problematic.

Improper hand counting is often extremely expensive, ineffective and inaccurate.

Just one day into the Nye County hand count, County Clerk Mark Kampf found a discrepancy of nearly 25% between the hand count and the machine count, a discrepancy that was attributed to human counting error. Kampf acknowledged after the hand count concluded that it “was marginally more accurate” than the machine tabulation.

Additionally, a Wisconsin study found that ballot counts originally conducted electronically were, on average, more accurate than votes that were tallied by hand counting.

Hand counting becomes a problem when election officials’ calls for it are not out of necessity but rather as a result of conspiracy theories. What Verified Voting calls election night hand counts — where all ballots are hand counted and the process starts on Election Day — leads to even more distrust in the system. Hand counting en masse, when the method is unnecessary, rushed and inaccurate, is a dangerous way to approach tallying election results.

The process is so arduous that a “York County, Pennsylvania audit of two races on 1,842 ballots took county staff four hours—a process that would have taken nearly 17 days of round-the-clock counting to count all races on all of the county’s 184,594 ballots.”

The report also points to Kern County, located in the southern end of the Central Valley and home to more than 388,000 registered voters, which estimated costs for hand counting the 2022 midterm elections at close to $1.9 million with labor demands of 920 staff. The county calculated the hand count would take more than 100,000 hours.

Esmeralda County, the least populous county in Nevada, provided another telling real-world example of the laborious effort it takes to hand count. A few election workers and two county commissioners needed more than seven hours to hand count just 317 ballots.

Verified Voting recommends hand counting be used only in certain necessary situations.

The report urges for the use of voting machines in the vast majority of instances. Machine counting is the dominant method of counting ballots across the U.S., and machines allow for results to quickly be tabulated and distributed to the public, which helps ensure public trust in elections and that certification deadlines are met. Voting machines have a big task on their hands — the U.S. has the longest ballots of any democracy in the world.

Machine counting isn’t only quicker, but also more cost effective, a reality that is crucial given that our elections are chronically understaffed and underfunded.

In its report, Verified Voting makes a clear distinction between hand counting all ballots and hand counting in order to confirm election results in the form of post-election audits. Post-election audits feature transparent hand counts that take place days after the election, involve batches of ballots and are provided ample time to complete.

More than 99.8% of registered voters live in areas where votes are counted electronically. The remaining voters who count all ballots by hand are able to do so because of their extremely small jurisdictions — most have less than 1,000 registered voters. Verified Voting recommends that counties that already effectively hand count to continue doing so as long as the process does not become too strenuous for election workers.

Hand counts can also work to catch the extremely rare instances where vote machines run into errors. To date, no example exists where this was needed in more than one county, according to Verified Voting.

With growing calls for hand counting by red-leaning counties, it will be crucial that states and local election offices throughout the country stay steadfast in ensuring ballots are only counted by hand in the limited circumstances where experts have deemed the process necessary.

From Arizona to California, the calls for hand counting are growing heading into the 2024 election cycle. Just last week, supervisors in Mohave County, Arizona narrowly voted against hand counting all 2024 ballots — though Mohave didn’t let the conspiracies win, there’s no telling that another county like Cochise won’t try again in the months ahead.