Nearly 70 Bills Introduced To Restore Voting Rights After Felony Conviction

On Tuesday, the Minnesota state Senate sent a bill to the governor that would restore voting rights to individuals with past felony convictions immediately upon release from incarceration. Under current law, individuals lose voting rights until the completion of their entire sentence, which includes parole, probation or community release and can stretch for years or decades after they return to their communities.

This is one of the first bills that has sailed through Minnesota’s Legislature, newly-controlled by Democrats, and the first piece of legislation in 2023 to restore voting rights statewide. It heads to Gov. Tim Walz (D) for his near-certain signature.

Since the 2020 election, a surge of legislation restricting voting access has moved through state legislatures. In 2023, anti-voting bills remain a fixture in Republican states across the country. Yet, there is one voting policy area where proposed legislation has been overwhelmingly positive: improving felony disenfranchisement laws to restore voting rights to formerly incarcerated individuals.

As of Monday, Feb. 20, at least 73 bills related to felony disenfranchisement have been introduced in over 20 states. Of these 73 bills, 68 of them ease existing felony disenfranchisement laws to differing extents. The remaining five bills look to make the laws more restrictive. This means that 93% of bills related to voting rights in the criminal legal system move in the pro-voting direction, a stark comparison to other policies governing voting access.

Felony disenfranchisement laws have racist origins, but states have largely moved in the right direction, albeit slowly, over the past two decades.

Felony disenfranchisement laws have a well-known racist origin, adopted soon after Black men were granted the right to vote in 1870. At the same time that states enacted felony disenfranchisement laws, lawmakers expanded legal codes that over-incarcerated African Americans. Since then, explosive prison and jail population growth — increasing by over 500% over the past 50 years — means that 2% of the voting-age population in the United States is excluded from political participation.

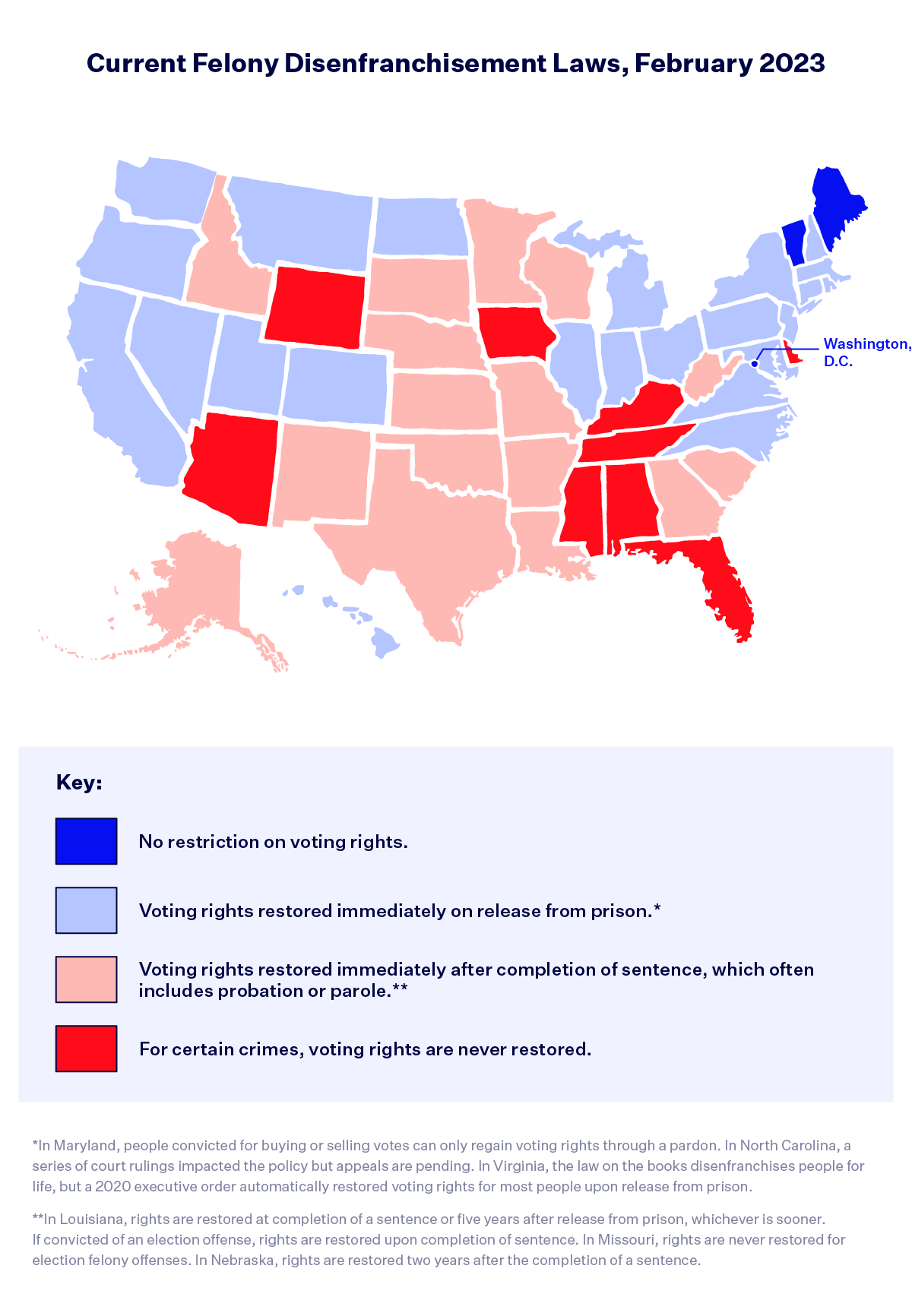

A 2003 study found that states with larger nonwhite prison populations are more likely to adopt the strictest of felony disenfranchisement laws. Today, in eight states — Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, South Dakota, Tennessee and Virginia — 10% of Black adults are disenfranchised.

From 1997 to 2020, 25 states and Washington, D.C. expanded eligibility, streamlined the restoration process or improved voter education. This includes several states that have repealed or amended their lifetime ban on voting for people convicted of felonies.

In Maine, Vermont, Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico, all citizens can vote in prison, regardless of their conviction status. These are the least restrictive policies in the nation. Washington, D.C. is the most recent jurisdiction to end felony disenfranchisement altogether, passing its law in summer 2020.

In the other 48 states, the laws range from restoring voting rights for all incarcerated individuals automatically after prison to restoring voting rights after the completion of an entire sentence (including probation and parole) to permanently disenfranchising certain people for life, except if they seek a specific exemption.

So far in 2023, at least 68 rights restoration bills have been introduced in 19 states.

As of Feb. 20:

- There are 20 bills in 10 states that would end felony disenfranchisement altogether. This is a large jump and would align the policy in these 10 states with Maine, Vermont and Washington, D.C.

- There are 22 bills in seven states that would restore voting rights immediately after incarceration, including the successful bill in Minnesota. If passed, these bills would align these seven states with the policies over 20 other states.

- There are 16 bills in three states that would restore voting rights after individuals complete their sentences, including post-incarceration release. These proposals are in Arizona, Kentucky and Mississippi, three states with the strictest policies that disenfranchise certain individuals for life, except if they specifically seek restoration. In the case of Kentucky, individual voters have only had their rights restored over the past few years thanks to executive action by the governor.

- There are 10 bills in five states that would make other improvements, such as eliminating a requirement to pay all legal fees and fines prior to restoration (Tennessee House Bill 687 and Senate Bill 730), removing Nebraska’s two-year waiting period after the end of one’s sentence (Nebraska Legislature Bill 20) or limiting disenfranchisement to felony convictions in Missouri, one of the few states where individuals can lose voting rights while incarcerated for a a misdemeanor (Missouri Senate Bill 376).

Of these bills, most propose changes to state statute. However, there are 12 bills in eight states (Arizona, California, Georgia, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New York and Virginia) that would make these changes through constitutional amendments instead. If passed, proposals to amend the state constitution would typically have to go before voters before enactment.

By Corey “Al-Ameen” Patterson, chair of the African American Coalition Committee.

Additionally, not included in the total 68 bills easing felony disenfranchisement policy, there are 13 pro-voting bills that would streamline voter registration or improve information sharing for formerly incarcerated individuals. Another six bills would facilitate jail-based voting for eligible incarcerated voters, meaning people held for pretrial detention or in most states, people convicted of misdemeanors.

“The tale of two trends:” There exists a divide between successful reforms and the immense amount of work yet to be done.

Minnesota has already succeeded this session, the result of years of advocacy by community groups. “I’m a spouse, a husband, a proud father of a 14-year-old daughter. And like some of you, I’m a businessman, a homeowner…I am a leader in my community,” a formerly incarcerated Minnesotan explained at a January hearing about Minnesota’s bill. “But unlike you I don’t have a voice. Unlike you, I’ve been made to feel like a second class American, because I can’t vote.”

New Mexico is another state where reforms are likely to prevail. But, the high volume of introduced bills across the country doesn’t necessarily translate to legislation moving forward and getting enacted elsewhere.

“I really see this as the tale of two trends,” Christopher Uggen, professor in Sociology, Law and Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota, told Democracy Docket. “On the one hand, more states have extended voting rights to include people convicted of felonies, reenfranchising approximately 1.5 million people since 2016. On the other hand, over 4.6 million people remain disenfranchised in the United States — or about the same number that we estimated in 2000.”

In Mississippi, 13 bills introduced in January 2023 would have made a meaningful difference in a state that has one of the most restrictive felony disenfranchisement laws in the country. According to a 2020 report, 16% of the state’s Black voting age population is locked out of political participation. Yet, the 13 potentially life-changing bills have already all failed in committee. An additional Republican-sponsored voter purge bill did succeed and contains a provision automatically restoring rights to certain disenfranchised veterans. This narrow bill passed the Mississippi House.

Felony disenfranchisement laws aren’t changing in just legislative chambers, but courtrooms too. Within the past year, courts have upheld policies in Minnesota and Mississippi. A series of court rulings expanded North Carolina’s restrictive law but it remains on the chopping block on appeal before the North Carolina Supreme Court, which recently flipped from Democratic to Republican control in the 2022 midterm elections.

“There are also states (such as Florida) that have stepped up prosecution for unlawful voting, which can result in new felony charges,” Uggen added. “The latter development could have a chilling effect on turnout even in places where people regain the right to vote.”

In a trio of deep blue states — California, Massachusetts and New York — there are proposals to enact constitutional amendments to end felony disenfranchisement altogether. Even with Democratic trifecta governments, the possibility for passing such reforms, which would enable these states to join Maine, Vermont and Washington, D.C. in ensuring no person loses their right to vote on account of a criminal conviction, is not guaranteed. “This session, our goal is to get the State House to move legislation forward,” explained Kristina Mensik, an organizer with the Massachusetts-based Democracy Behind Bars Coalition. “But we want to bring everyone with us — we hope to center rights restoration in the mind of the Massachusetts public and the policy priorities of advocacy groups.”

The public, lawmakers and activists have gathered momentum around this policy area in recent years, yet proposed laws likely won’t advance this session in large swaths of the country, meaning millions will remain locked out of the political process.

“In 2006,” Uggen continued, referring to the year he wrote a book about this topic, “we were optimistic about reforms, believing that the door blocking voting rights was barely hanging by its hinges. But it’s taken a lot longer than we anticipated and the reforms have been more piecemeal around the country.”