How Voter List Maintenance Becomes Voter Purging

Back in February, we wrote about how Republicans are purging noncitizens from the voter rolls in Texas — an act that also threatened to endanger the registrations of eligible voters. In today’s piece, we’re taking a step back to talk about voter purges more generally. What are they? Why do they happen? And more importantly, why are they dangerous? We answer these questions and demonstrate how Republicans could use voter purges to suppress the vote.

Why do states remove people from the voter rolls in the first place?

Like other nefarious voting practices, voter purges have roots in a legitimate need. In nearly every state, eligible voters have to register with their state elections offices before they can cast their ballots. But when voters die, move to other states or otherwise become ineligible to vote, their voter registrations become outdated. If states don’t remove these invalid registrations, the voter rolls then become bloated with tons of outdated information.

To remedy this, the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (NVRA) permits states to remove voters who request it, voters who are mentally incapacitated and voters who have been convicted of a crime. Additionally, the NVRA requires states to maintain a general program of list maintenance to remove voters who have died or have moved.

Unfortunately, there isn’t a simple way for states to go about removing outdated registrations. We don’t have a national database of registered voters, for instance, or a national ID system that lets states immediately confirm eligibility or track residency changes. States are left to make do by trying to systematically use other data sources to identify voters that should be removed, such as change-of-address forms from the U.S. Postal Service or DMV records. States also set up two databases for sharing information:

- The Interstate Voter Registration Crosscheck Program (Crosscheck), which has since been shut down due to a settlement in a lawsuit over data privacy concerns

- The Election Registration Information Center (ERIC)

All of these data sources and the methods states use to match them with the voter file are prone to errors, which can lead them to wrongfully flag eligible voters for removal. For example, an eligible voter could share the same name with a voter who has died in that same state and could be removed simply due to this coincidence. While the NVRA has some safeguards in place to protect eligible voters by limiting removals close to an election and requiring states to follow a specific process to remove voters, its protections aren’t perfect and states don’t always comply. These vulnerabilities allow bad actors to exploit list maintenance to purge eligible voters — who may not know they’ve been removed until they try to vote in the next election at which point it’s too late to re-register if the state doesn’t allow same-day registration.

When does list maintenance become a voter purge?

Since the NVRA requires states to remove ineligible voters from their voter rolls, there’s no hard and fast rule for determining when list maintenance becomes a purge — i.e., when eligible voters are being improperly removed en masse. When a list maintenance program removes large numbers of actually eligible voters, or when it target voters in a discriminatory manner, that suggests something has seriously gone wrong.

In 2013, for example, Virginia tried to remove thousands of voters using data pulled from Crosscheck. When the state sent counties the list of names to remove, however, county officials discovered error rates as high as 17%. It turned out that Virginia hadn’t checked the data for accuracy and many voters were wrongly flagged as having moved from Virginia to another state when they had actually done the opposite and moved from another state to Virginia. Many of the voters who were accidentally removed had to vote using provisional ballots that weren’t counted until well after Election Day in 2013, adding to controversy in that year’s extremely close race for attorney general.

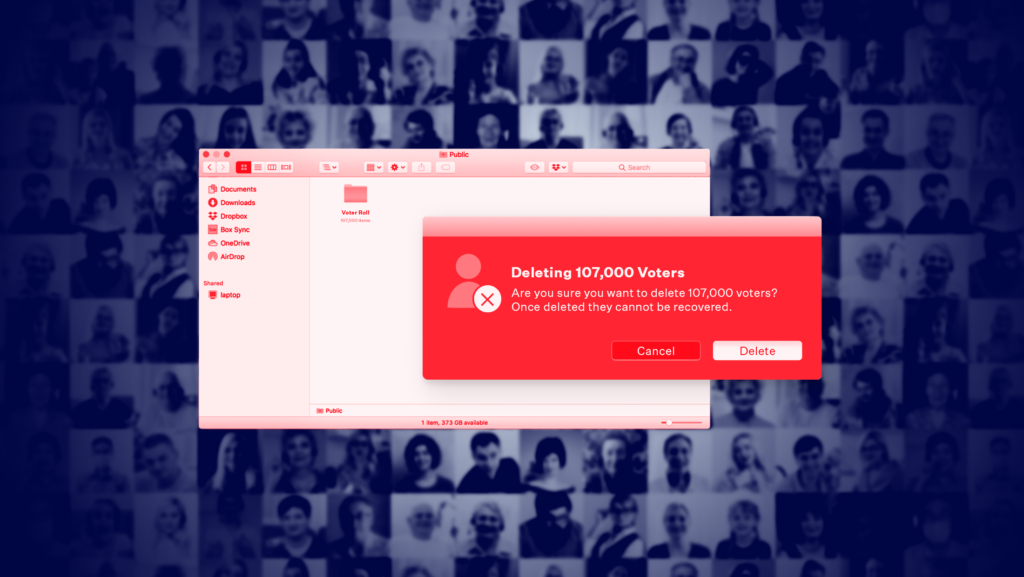

Purges that target voters for not voting are particularly controversial. In 2017, Georgia removed 107,000 voters simply because they hadn’t voted in recent elections. There’s nothing to suggest these voters were no longer eligible — Georgia and states with similar policies just decided to assume that if someone doesn’t vote in a few elections then that’s sufficient evidence that they’ve moved and should be removed from the state’s rolls. Alarmingly, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2018 that this practice doesn’t violate the NVRA, expanding the scope by which purging can occur. As a result, voters in some states are now in danger of losing their right to vote simply because they chose not to exercise it for whatever reason — and these voters are more likely to be minorities or low income since likelihood of voting is strongly correlated with income and race.

How are Republican-led states using voter purges to suppress the vote?

In recent years, Republicans have been weaponizing purges and removing significant numbers of otherwise eligible voters from the voter rolls. Prior to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2013 ruling in Shelby County v. Holder, jurisdictions with a history of discriminatory voting practices had to obtain approval that any change, including a voter purge, would not harm minority voters. The Court’s decision dismantled this process and previously covered jurisdictions no longer needed to obtain approval. Since then, Republican-led governments in states like Georgia and Texas increased purge rates more than states that weren’t required to seek approval prior to Shelby. Additionally, as purges increased, the number of people who were forced to vote via provisional ballots because their names weren’t on the voter rolls also increased — evidence that many eligible voters were improperly removed and were in danger of not having their vote counted.

Republican-run states have also been scouring the voter rolls for noncitizens that somehow end up registered and purging their registrations. This is what Cameron County, Texas was doing when we wrote about it in February. More and more states have passed laws requiring officials to identify and remove noncitizens from the rolls even though there’s no evidence that noncitizens vote in any significant number in U.S. elections. Like other forms of purges, targeting noncitizens often relies on flawed data or methodologies that can improperly flag valid registrations. In Texas, the burden fell disproportionately on naturalized citizens and voters of color — demonstrating again the inherent dangers in list maintenance. Coupled with the Supreme Court’s 2018 decision permitting the removal of infrequent voters, minority, low-income and naturalized voters are at a significant risk of having their registrations canceled.

While removing ineligible voters is a necessary and legally required part of administering elections, this practice, when done irresponsibly or with nefarious intent, can lead to eligible voters having their registrations canceled. If a voter who has been removed from the rolls doesn’t find out in time, they might lose their right to vote completely. Without proper safeguards in place, purges are liable to be used to suppress the vote and even influence election outcomes. There’s much more to say on this topic than we can cover in one day, so stay tuned for future content from us.