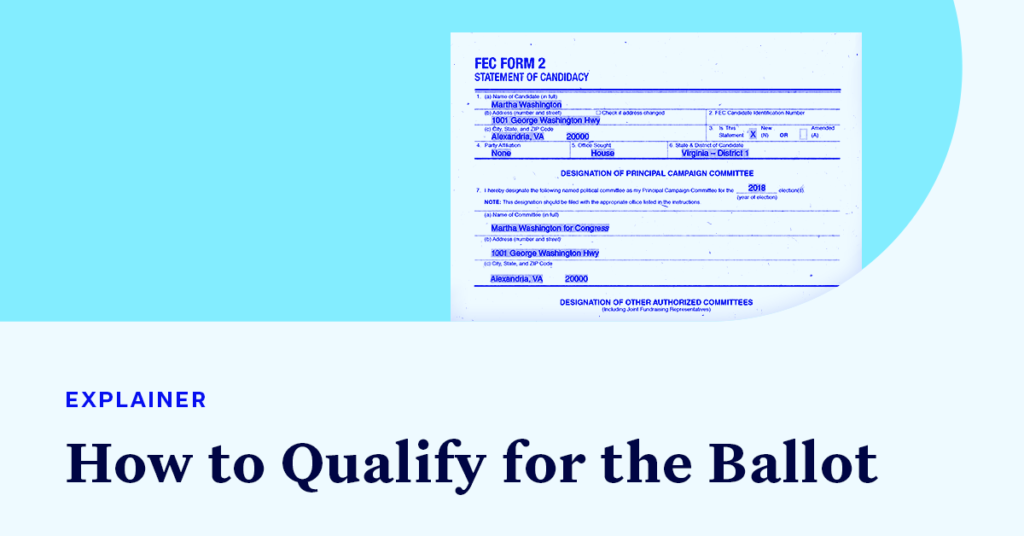

How to Qualify for the Ballot

Inspired to run for office? One of the first steps in any political campaign is qualifying for the ballot so that your fellow citizens can vote for you. But how do you get your name on the ballot in the first place? In today’s Explainer, we break down how candidates can qualify for the ballot for the general election. While exact requirements are different in every state, most states have broadly similar processes.

There are three main ways to qualify for the general election ballot:

1. Win the nomination of a political party.

The most common way for a candidate to be placed on the ballot is by winning the nomination of a political party. Aside from third-party or independent candidates (more on that later), candidates for office are almost always Democrats or Republicans. Once you win the nomination from one of these two parties, you’re automatically added to the general election ballot in most states. So the question then becomes how do you win a party’s nomination?

Usually, you win the nomination by winning a party’s primary election. You can qualify for the primary ballot a few different ways:

- In some states, like in Missouri and Alabama, you just need to file with the state’s elections office by completing any required paperwork and paying any fees. Some states that require filing fees will waive them if you submit a petition — in Kansas, for example, you can qualify for the congressional primary without paying the $1,760 fee by getting the signatures of 2% of party members in your district.

- In others, like in Illinois and Maine, you must submit a petition with a certain number of signatures from voters registered with the same political party. The required number of signatures varies by state. In Maine, for example, if you want to get on the primary ballot for the U.S. House you must collect 1,000 signatures from registered Democrats in your district.

- Finally, some states, like Colorado and Connecticut, have party conventions where the party chooses candidates for the primary election, although unselected candidates can still qualify for the primary ballot by submitting a petition.

Smaller political parties that don’t hold primaries typically nominate their candidates through caucuses or conventions.

A few states, like California and Louisiana, have “jungle primaries” where all candidates, including independents, run on the same ballot. In these states, the process for getting on the primary ballot is the same for every candidate, regardless of party — you must file a petition by collecting a certain number of signatures and complete any other required paperwork. In other states, like Virginia, parties can choose to not hold primaries at all and pick their nominees at a convention.

2. Petition for ballot access as an independent candidate.

If you’re a political independent or unaffiliated with a party, you can qualify for the ballot by petitioning for ballot access. This involves submitting a list with a set number – or certain percentage – of signatures of voters in the district where you’re running. Again, the exact number varies, but the threshold is typically higher for offices that represent more people like governor or senator. For example, in Alabama, an independent candidate needs a number of signatures equal to 3% of the votes cast for governor in the district in question. Some states, like Arizona, require independent candidates to collect signatures only from other unaffiliated or independent voters. Other states allow any registered voter, regardless of party, to sign an independent candidate’s petition.

The required number of signatures is usually higher for independent or unaffiliated candidates than the number required to make it onto a political primary ballot. For instance, to run as an independent for a statewide office in Illinois, you need 25,000 signatures. To run in the primary for a statewide office, on the other hand, you just need between 5,000 and 10,000 signatures. As a result, qualifying for the ballot as an independent is much harder than running as a candidate registered with a major political party.

Many states also have “sore loser” laws that prevent someone who lost the nomination of a political party from petitioning for ballot access as an independent candidate. Other states, while not prohibiting this explicitly, have other rules that effectively prohibit candidates from running as independents if they’ve lost their party’s primary, such as deadlines to petition for the general election ballot that fall before the date of the state’s primary election.

3. Run as a write-in candidate.

The last option is the simplest. All states save for Hawaii, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nevada, Oklahoma and South Dakota allow voters to write in the name of a candidate on their ballot. So, if you want to run for office but fail to win a party nomination or don’t collect enough signatures to get on the ballot as an independent, your last resort is to ask people to write your name on the ballot when they vote.

Running as a write-in candidate isn’t always as simple as just asking people to write your name on their ballot, however. Most states that allow write-in candidates also require that write-in candidates register with the state before the election in order to be counted. In these states, votes for write-in candidates that are not registered beforehand are discarded.

While uncommon, write-in candidates do win elections. In 2010, for instance, Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R) successfully won re-election through a write-in campaign after losing the Republican primary to a Tea Party challenger.

Qualifying for the ballot can be costly and time-consuming.

Overall, getting on the ballot isn’t a very simple process. States place many requirements on ballot access in order to limit the number of candidates who can qualify— even running as a write-in candidate often requires jumping through a few hoops. These barriers are even higher for independent candidates who want to be placed on the ballot. If you’re serious about running for office, be prepared to expend effort and resources on just the first step of the campaigning process — let alone everything that comes after.