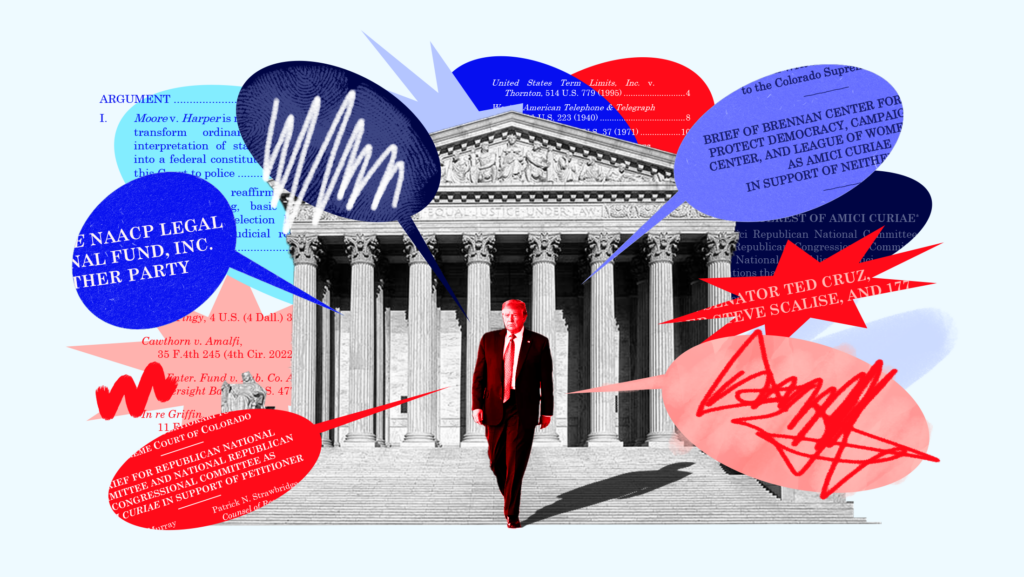

How Should SCOTUS Apply Section 3 of the 14th Amendment? Amicus Briefs in Trump’s Disqualification Case Have Different Answers

This week, the nation’s highest court will hear one of the most consequential court cases of this election cycle.

In the final weeks of 2023, the Colorado Supreme Court propelled the nation into “unchartered territory” after finding that former President Donald Trump is disqualified from holding the office of president under Section 3 of the 14th Amendment and ordered his removal from the state’s Republican primary ballot.

Trump appealed this decision, asking the U.S. Supreme Court to determine if the Colorado Supreme Court erred in its decision to remove him from the ballot. The Colorado Supreme Court has paused its decision until the nation’s high court makes a final determination in the case. As Trump battles 18 challenges to his eligibility under Section 3, all eyes will be on the Supreme Court this week as its decision will impact challenges across the county.

Over the last few weeks dozens of amicus — or “friend-of-the-court” — briefs have been submitted by members of Congress, state officials, political organizations, professors and historians — all seeking to make their mark ahead of oral argument this week. Here are some of the highlights from some of the briefs filed.

Some Republicans are adamant that the questions of Trump’s eligibility should be determined by Congress, not state courts or state officials.

One of the questions ahead of Thursday’s argument centers around the implementation of Section 3 of the 14th Amendment. Trump’s Republican defenders are adamant that the determination of the former president’s eligibility does not belong in the hands of the state officials or state courts.

179 congressional Republicans — over two-thirds of GOP members in both the House and Senate — argued that the Colorado Supreme Court intruded upon Congress’ authority to enforce Section 3. They assert that before anyone can enforce the provision, Congress must pass implementing legislation — or legislation that lays out the details for how the law will be enforced. Republicans in Congress claim that they have access to the best resources and can conduct a level of investigation that other entities cannot: “Congress, representing the Nation’s various interests and constituencies, is the best judge of when to authorize Section 3’s affirmative enforcement.”

The Republican National Committee (RNC) and National Republican Congressional Committee’s (NRCC) amicus brief echoes similar concerns, arguing that Section 3 does not give state officials and state courts the power to “frustrate the federal government or national will.”

Under their theory, the power of Section 3 was never meant to be wielded by the states. In fact, they allege that at the time of the drafting of the 14th Amendment, it would not have made sense to give power to state officials or state courts, since they were the very threat the Framers were seeking to neutralize. The RNC alleges that allowing state officials to enforce Section 3 “would court anarchy” and “would destroy that confidence, threaten this Nation’s system of representative democracy, and unravel the Reconstruction Congress’s design.” Additionally they point to past implementing legislation under Section 3 that did not include enforcement by private litigants.

Eleven Republican secretaries of state also chimed in to say that it is not within their authority to disqualify a presidential candidates, stating that if Congress had intended for states to exercise such authority “it could have drafted language that similarly imposed an affirmative obligation on the States to exercise the disqualification power that Section Three mentions.”

Amicus briefs from the NAACP and Professor Sherrilyn Ifill provide historical context around the 14th Amendment and draw parallels between 1868 and now.

Both the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and its former president and current law professor, Sherrilyn Iffil use their briefs to discuss the historical context surrounding the 14th Amendment. Set in the wake of the Civil War and assassination of President Abe Lincoln, the NAACP asserts that the 14th Amendment was created to “unite a divided citizenry, and enshrine a lasting commitment to a newly multiracial democracy.”

Ifill — a civil rights lawyer and scholar — encourages the Court not to dismiss the significance of Section 3, since it “plays a vital role in the overall architecture and integrity of the 14th Amendment.” Tasked with bringing the nation together, the drafters of the 14th Amendment considered two threats: resistance to Black citizenship from southern states and the reality of former Confederate loyalists returning to political power across the South.

The proliferation of violence against Black people and discriminatory laws enacted across the South created a disturbing picture of “active opposition to the status” of free African Americans. Simultaneously, former insurrectionists were being appointed and re-elected to state and federal governing positions throughout the South. History recorded a general anger toward Black people and the Confederate defeat, something that Frederick Douglass recognized “would ‘not die out in a year’” or in a generation. The drafters of the 14th Amendment saw Section 3 as crucial in guarding against anti-democratic sentiments and “the re-establishment of political power by former insurrectionists.”

The NAACP argues that the intent behind Section 3 should not be confined to the past. They contend that events surrounding Jan. 6, 2021 — including questioning the election results in Black and brown communities — were intended in part to “undermine the voting rights” of Black voters.

Ifill concludes her brief with: “by targeting and seeking to disqualify legitimate votes cast by Black voters to fuel his effort to overturn the results of the presidential election, former President Trump’s insurrection touched on key concerns of the 39th Congress in its drafting of, and deliberations about the 14th Amendment.”

A few amicus briefs remind the court that it is not “undemocratic” to adhere to the U.S. Constitution by disqualifying Trump.

Trump’s campaign has referred to the effort of Colorado voters to disqualify him under Section 3 of the 14th amendment as “undemocratic”. Some argue that he is a popular candidate and disqualifying him would undercut the democratic process. Common Cause reminds the Court that the Constitution possesses checks and balances for the very expressed purpose of preserving constitutional order. Their brief highlights many restrictions on who voters can select including restrictions on age and term limits. They aver that elections must follow the rules laid in the Constitution and the Court must not shy away from public pressure to ignore their duty to the Constitution. The Framers of the Constitution recognized that protecting democracy would require “uncommon portion of fortitude” when going against “the major voice of the community,” Common Cause argues

Emory University professor Carol Anderson and University of Denver Sturm College of Law professor Ian Harrell — both academic scholars and advocates for racial justice — also contend that Trump’s claims that this 14th Amendment challenge are “antidemocratic” fail in comparison to his actions leading up to the Jan. 6, 2021 insurrection. Anderson warns that Trump’s attempt to disenfranchise voters across the country and his push for courts to ignore the Constitution are equally dangerous. Trump’s actions require a constitutional response, Anderson emphasizes.

Several pro-democracy organizations pushed back against the assertion of a radical legal theory espoused by Trump’s legal team.

Nestled at the end of Trump’s brief in this appeal is an argument that relies on independent state legislature theory (ISL), a right-wing constitutional theory about who has the power to set rules for federal elections. Trump argues that the Colorado Supreme Court misinterpreted its states’ election code in violation of the will of the state legislature, and in doing so, contravened the Electors Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

The Brennan Center along with other pro-voting orgs warn the Court that Trump and Republicans are using this case to reassert the ISL theory. In Moore v. Harper, the Court rejected the theory and maintained that state courts are the best place to review state laws governing federal elections.

In their brief, pro-voting orgs assert that Moore provided for federal judicial review only when state courts “‘transgress the ordinary bounds of judicial review such that they arrogate to themselves the power vested in state legislatures to regulate federal elections.’” They maintain that the Colorado Supreme Court did not step outside the ordinary bounds of judicial review. By entertaining this argument, they fear that the Court would provide federal courts “a free-wheeling license to second guess those interpretations.”

Oral arguments will take place before the U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday at 10 a.m. EST. Find out everything you need to know about Trump and the 14th Amendment here. We will provide live updates during oral argument here.