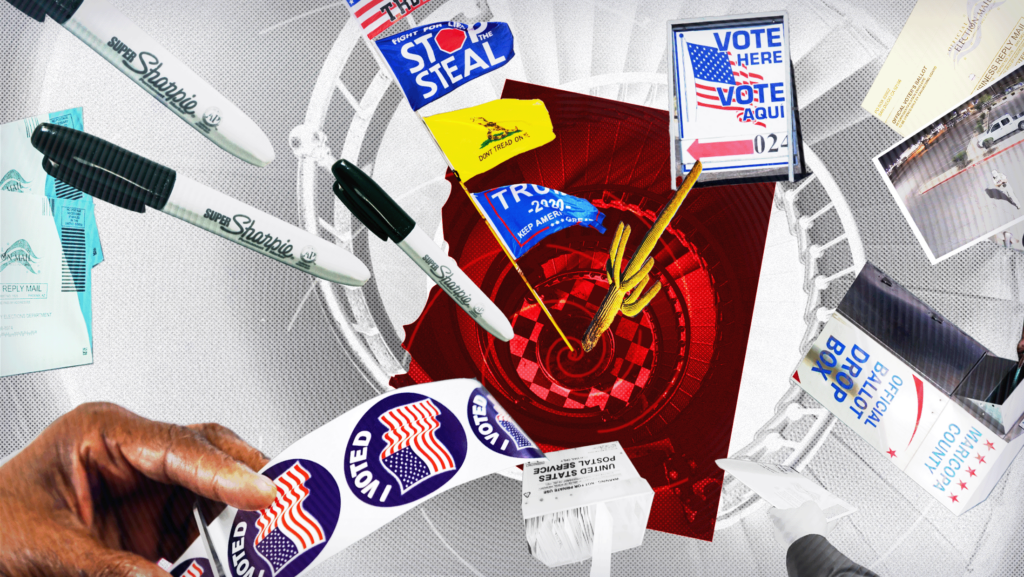

How Arizona Became the Epicenter of Election Conspiracy Theories

When Gabriella Cázares-Kelly started her job as the Pima County Recorder in early 2021, her workplace “was a quiet, sleepy office that nobody really cared about,” she said.

It didn’t last long.

Months after taking office, Cázares-Kelly, who was elected to the position in November 2020, became inundated with media requests, accusations of election fraud and — most concerningly — threats and harassment. It was fallout from the 2020 election, in which former President Donald Trump and his sycophants refused to accept that he lost the race and callously spread dangerous conspiracy theories about election fraud.

Cázares-Kelly thought the pandemonium would eventually settle and she could administer the 2022 midterm election without so much noise.

Arizona, a key swing state this election cycle, remains an epicenter for voting rights litigation with 20 lawsuits filed this cycle.

Sign up for our free newsletters so you never miss a new lawsuit or court decision that could impact who takes the White House on Nov. 5.

The calm never came.

“I kept waiting for things to die back down and normalize again to the sleepy quiet office that I first ran for,” she recalled. “I think I finally came to the realization that the face of elections has changed permanently. I think there’s been a permanent change because of the 2020 election and the level of scrutiny and concern.”

Since 2020, when Trump and the GOP promoted dangerous conspiracy theories and made false claims of mass voter fraud, Republicans in key swing states have been embroiled in an ideological civil war between moderates and the party’s far-right extremists. In Georgia, for example, the state’s Republican Gov. Brian Kemp — who has his own rich history of far-right extremism — has been decidedly castigated by Trump and the party for not helping the former president cheat in the 2020 election — all the while MAGA loyalists have taken over the State Election Board (SEB) and are trying to rewrite election rules to help Trump. And in states like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, the Republican Party is similarly seeing this ideological battle play out.

That ideological tug-of-war is absent in Arizona. Instead, far-right extremists have taken over the state’s Republican Party and — four years later — the Grand Canyon State is still the epicenter of election conspiracies, harassment toward election officials and an all-out assault on voting rights from the Arizona GOP. According to Democracy Docket’s litigation database, there have been 18 anti-voting lawsuits filed in Arizona in the 2023-2024 election cycle — the highest number of any state.

The attack on voting rights isn’t just from litigation. Over the past four years, the Republican majority in the state legislature have introduced a barrage of anti-voting bills. “In 2020 there were 80 election bills introduced into the state legislature, which was high compared with previous years,” Cázares-Kelly said. The year before, she said about 50 anti-voting bills were introduced and then “maybe 10 a year” on average in previous years. In 2021, the state legislature introduced 183 election-related bills. “Our office was inundated with people calling to ask… is this a good bill or a bad bill?” she said. “I’m like, I don’t even have time to read so much of these bills.”

With mere days until the general election, Cázares-Kelly and her staff are working overtime to ensure this year’s election isn’t a repeat of the past two. “We’re tired, but for the most part we’re in good spirits,” she said.

But when she has a few moments to spare, a lingering question gnaws at her: How did Arizona get this way?

A right-wing message of hate resonates as demographics shift

It’s impossible to pinpoint the exact moment when and how the conspiracy theories began to take a hold in Arizona. As a key swing state in 2020, Trump narrowly won the state in 2016 by only three-and-a-half points. There’s an argument to be made that the state’s more diverse population growth led to its Democratic shift in 2020.

“There’s a lot of influx of people coming in,” said George Arredondo, who’s running for Pinal County Supervisor. Arredondo said that, while there’s a fair share of retirees and older people who may read into these dangerous conspiracy theories who relocated to Arizona, the state has also seen a diverse influx of younger people. “You have a cluster of people leaving higher cost areas. They’re younger. They want jobs, things like that,” he said. “So we are kind of transitioning. And I think transitioning from a dark red to a light red to ideally purple or blue. That’s because of the growth that’s been coming in.”

Arredondo is running for the seat soon to be vacated by Pinal County Supervisor Kevin Cavanaugh who has a history of promoting election conspiracy theories — including unproven allegations of voter fraud in his recent failed bid for sheriff. He sees elected officials like Cavanaugh as a threat to democracy, which is why he jumped into the supervisor race.

Much like Arredondo, Anne Carl is running for office in her community of Cochise County because of the state’s far-right shift. She’s hoping to unseat Cochise County Recorder David Stevens, another avowed election denier who tried to circumvent state law to hand count midterm election ballots.

“Cochise County’s political landscape has indeed shifted over recent election cycles, with a rise in far-right ideologies and conspiracies,” she said. “It’s concerning, not just for the future of Arizona, but for the health and safety of our small communities everywhere and country and world as a whole.”

She cited the familiar reasons for the national GOP’s extremist shift under Trump: National movements and figures who prioritize divisive rhetoric over unity and cooperation. Failure from the mainstream media, who prioritize sensationalism over reporting facts, along with fewer people reading and supporting local publications. And disinformation campaigns from foreign adversaries trying to sow discord in the U.S. And, in campaigning through Cochise County, she sees the real-world effect of all this.

“I’ve been struck by how many households have ‘Unwelcome’ mats and customized mean, cynical life-threatening signs hanging on their front doors,” she said. Many say some version of: “Go on ‘n git or be shot.”

But Carl, a longtime Arizona resident, isn’t so sure why the GOP’s far-right drive seems to be more pronounced in her state than in others. She cites the “economic and social challenges many residents here face” that have been weaponized by extremists, which she said further escalates the scapegoating and division.

With the Arizona GOP’s extreme ideology at the forefront of the party, Carl emphasized that there doesn’t seem to be room for moderates, who instead find themselves increasingly switching parties. “Most Democrats in this part of Arizona are moderate like me,” she said. “We want a comprehensive border deal. We’re patriotic. We support veterans. We’re capitalists. We take a commonsense, pragmatic approach to government. We all want it to work long-term.”

Concerns for safety

There’s no better case for the idea that moderate Republicans don’t have a place in Arizona’s GOP than Maricopa County Recorder Stephen Richer. Richer, a Republican, was elected to his position at the same time as Cazares-Kelly, the Pima County Recorder. When he was elected, Cázares-Kelly recalled how Richer also flirted with 2020 election conspiracy theories.

“He came in in 2021, and it is not lost on me that he was also leaning into the conspiracy theories, and that’s how he unseated Adrian Fontes,” she said. “It was a very tight race, and he was also questioning the integrity of the election.”

When Richer got into office, however, he thoroughly investigated all the election conspiracy theories and decisively found that nothing untoward had taken place in the election of Arizona’s most populous county. But the state’s Republicans wouldn’t accept his findings and turned on him. In the years since he took office, Richer has been subjected to numerous threats of violence and harassment.

“He thought when he got in, he would be able to take a look around and say, ‘You know what, everybody there’s no fraud. We’re fine.’ And flames got away from him,” said Cázares-Kelly. “And then he spent the last four years trying to water down those flames, and it resulted in his party eating him alive.”

In July, Richer lost his primary reelection campaign to Justin Heap, a GOP member of the Arizona House of Representatives who, like many of the Republicans on the Arizona ballot in November, has a history of election denialism. The number of election deniers and far-right extremists on the ballot throughout the state — especially for positions that deal with election administration like recorder or board of supervisors — has Cázares-Kelly extremely concerned.

Though Richer’s made national headlines because of how he’s been castigated by his own party for simply following the rule of law, he’s far from the only election official to face harassment and threats of violence.

The Pima County Recorder’s office gets frequent harassing calls and threats, though Cázares-Kelly is quick to point out it’s nowhere near the level of Maricopa County, since Pima is a Democratic stronghold.

“What we tend to see is a lot of overt racism and white supremacy,” Cázares-Kelly said. “People will come and make comments when they drop off their ballots, or when they’re voting, to staff. Phone calls can just be atrocious. Sometimes we’ve had people call and say things like, ‘Oh are you the diversity hire?’ Or they notice somebody with a slight accent, and they’ll say something like, ‘Oh, I don’t talk to Mexicans.’ And then hang up the phone.”

With a little over a week to go until the election, Cázares-Kelly doesn’t have much time to reflect on how Arizona became like this or what could happen once all the ballots in Pima County have been counted. Like many election offices across the country, the rise of conspiracy theories, anti-voting measures and harassment has made her job harder — and the state’s budget for her office is barely enough to meet the moment.

Still, she’s worried about some of the people on the ballot that, should they be elected, she’ll have to work with.

“We’re all very fearful about some of these extreme candidates,” she said. “There’s one in Maricopa and there’s one in Yuma. The other recorders and I… we’re definitely worried about it. It’s very concerning.”