Following Supreme Court’s Voting Rights Act Decision, a Redistricting Case Out of Galveston County, Texas Heads to Trial

On June 8, 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Allen v. Milligan to preserve the current application of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA), a crucial federal provision that protects against racially discriminatory voting laws and electoral practices. Almost two months later, on Aug. 7, 2023, a federal district court will hold a trial in a local redistricting lawsuit out of Galveston County, Texas involving claims brought under Section 2 of the VRA.

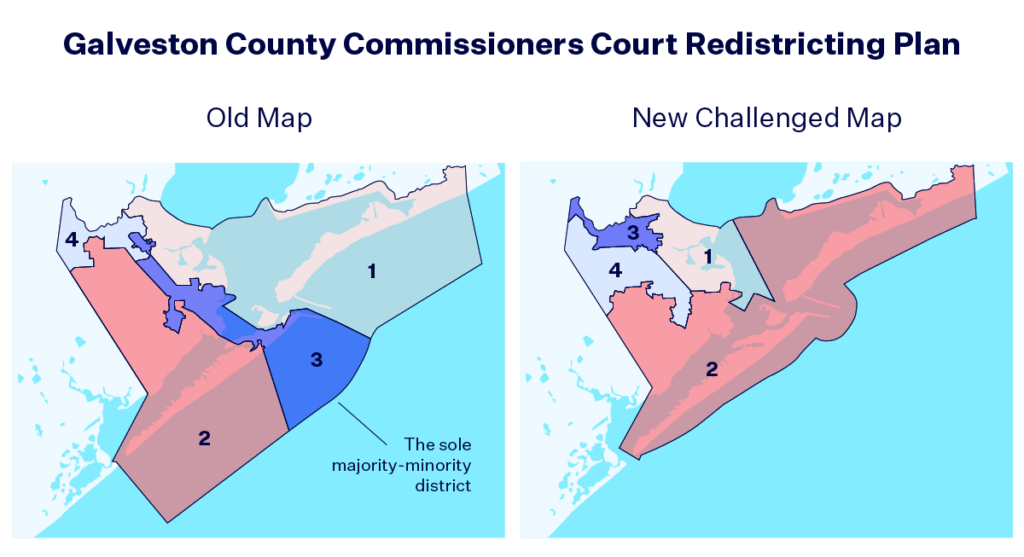

The consolidated case, Petteway v. Galveston County, challenges the 2021 redistricting plan for the Galveston County Commissioners Court, alleging that it discriminates against the county’s Black and Latino voters and dilutes their electoral influence. The Commissioners Court is composed of four commissioners who are elected via single-member districts called “precincts” and a presiding officer known as a county judge, who is elected at-large.

Serving as the county’s primary governing body, the Commissioners Court exercises substantial authority over policy-making, budgetary and infrastructure-related matters within the county. Despite accounting for nearly 40% of the county’s total population, Black and Latino residents do not constitute a majority in any commissioner precinct under the challenged redistricting plan.

As one of the first redistricting cases headed to trial following the Court’s Allen decision, the Petteway lawsuit signifies the reverberating impact of Allen on Section 2 redistricting litigation across the country. Indeed, the case is one of over 30 redistricting lawsuits bringing Section 2 claims that are currently active in federal court.

The Petteway lawsuit also serves as a reminder that the Allen decision does not only affect congressional and state legislative districts. It also bears upon redistricting at the city and county-level, where egregious instances of racial vote dilution harm voters of color by undermining their electoral power in local jurisdictions. With Section 2’s existing protections intact after Allen, the plaintiffs in the Petteway case have the opportunity to argue their claims against the county’s racially discriminatory map at a two-and-half week trial that begins today.

From 1975 to 2013, Galveston County was subject to federal preclearance requirements under the VRA.

The 2021 decennial redistricting process marked the first time in nearly four decades that Galveston County was free to alter its redistricting plans without federal oversight. Prior to the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder, the county was subject to federal preclearance requirements under Section 5 of the VRA. As a previously covered jurisdiction with a history of racial discrimination, Galveston County had to submit proposed changes to its redistricting plans and voting laws to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) or a federal court for approval.

While subject to the VRA’s preclearance regime, the DOJ twice objected to various redistricting proposals in Galveston County, initially in 1992 and again in 2012. In a 2012 letter interposing an objection to Galveston County’s Commissioners Court districts under Section 5 of the VRA, the assistant U.S. attorney general at the time wrote: “[W]e have concluded that the county has not met its burden of showing that the proposed plan was adopted with no discriminatory purpose.” The letter asserted that the county’s elimination of Precinct 3 — the sole majority-minority Commissioners Court district — would lead to a “retrogression in minority voting strength.”

As a result of the DOJ’s objection, a federal court ultimately ordered the county to enact a new redistricting plan that withstood federal preclearance and maintained the county’s longstanding majority-minority district. Under this plan, Black and Latino voters were afforded the opportunity to elect their commissioner of choice in Precinct 3 for the next decade.

No longer subject to preclearance during the 2021 redistricting process, Galveston County had carte blanche to enact a discriminatory map.

Following the release of 2020 census data, the Galveston County Commissioners Court was tasked with redrawing its four-precinct redistricting plan to account for population growth within the county. Rather than taking into consideration the substantial increase in the county’s Black and Latino voting-age populations over the past decade — which grew from a combined 33.2% to 35.6% — the Republican commissioners once again opted to dismantle Precinct 3. However unlike in 2011 — where Section 5 of the VRA was utilized to override the county’s discriminatory map — no such safeguard existed during the 2020 redistricting cycle that could preemptively halt the county’s discriminatory districts from going into effect.

Since 1999, Precinct 3 has been represented by Commissioner Stephen D. Holmes, who, in addition to being the only Democrat to currently serve on the Commissioners Court, was the court’s only Black member at the time of the 2021 redistricting process. As of 2020, Precinct 3 had a Black and Latino voting-age population of over 60%, a share that dropped by more than half following the 2021 redraw.

On Nov. 12, 2021, after holding only one public meeting on a set of proposed redistricting plans, the Commissioners Court voted 3-1 to enact a redistricting plan that “cracked” Black and Latino voters across all four precincts, thereby denying them the opportunity to constitute a majority and elect their candidate of choice in any precinct. The plan specifically moved Precinct 3 inland to northwest Galveston County to include portions of League City and Friendswood — two predominantly white areas — while splitting the much more diverse municipalities of La Marque and Texas City among multiple precincts. Holmes was the only commissioner to vote against the map, which was drawn without his input and rendered him unable to be reelected by voters in the newly composed Precinct 3.

According to reporting by local Texas news outlets and expert witness testimony, the Commissioners Court’s redistricting process occurred within a truncated timeline, and was characterized by a lack of transparency and opportunity for meaningful public comment and testimony. Nonetheless, Black and Latino voters, led by Holmes, turned out in droves to oppose the maps at the singular public meeting held in the middle of the afternoon on a weekday at a crammed and relatively remote location.

“It’s about the people of Precinct 3 being able to pick the candidate of their choice,” Holmes stated to the crowd at the Nov. 12 meeting. He continued:

It’s not just an election, this is their life. They fought this for years…We are not going to go quietly into the night…We are going to rage, rage, rage until justice is done.

Following the enactment of a new map, litigation ensued. A total of three lawsuits currently challenge the county’s redistricting plan.

In response to the enactment of the new Commissioners Court map, a group of Black and Latino Galveston County voters — many of whom used to reside in Precinct 3 — brought a federal lawsuit challenging the new redistricting plan. Led by Galveston resident Terry Petteway, the lawsuit alleges that the redistricting plan contravenes Section 2 of the VRA by “denying Black and Hispanic voters an equal opportunity to participate in the political process” and violates the 14th and 15th Amendments by intentionally discriminatory against minority voters. Additionally, the Petteway plaintiffs contend that “[r]ace predominated the drawing of Commissioners Court precinct lines…without a compelling justification,” consequently rendering the plan an unconstitutional racial gerrymander.

Relying on facts about the county’s sordid history of racial discrimination as well as the lack of public input regarding the Commissioners Court districts, the Petteway plaintiffs argue that the 2021 redistricting plan must be struck down prior to the next election and replaced by a map that retains the county’s former majority-minority district. According to the lawsuit, the enacted Commissioners Court redistricting plan is “substantially similar” to the one that failed to pass DOJ preclearance in 2012.

The lawsuit also points to evidence of racially polarized voting in the county — whereby the political preferences of the county’s minority voters significantly diverge from those of white voters — in order to support the assertion that Black and Latino voters will be deprived of any opportunity to elect their preferred candidate under the new redistricting plan.

Following the Petteway lawsuit, both the DOJ and a coalition of civil rights organizations — including local Texas chapters of the NAACP and the League of United Latin American Citizens — mounted additional legal challenges to Galveston County’s Commissioners Court districts. These two lawsuits were eventually consolidated with the Petteway case. While the DOJ’s case only brings claims of racial vote dilution under Section 2 of the VRA, the civil rights groups’ lawsuit mirrors the claims in the Petteway case, which include both Section 2 claims as well as constitutional claims pertaining to intentional racial discrimination and racial gerrymandering.

On the other side, the Republican commissioners defend the map as being “race-neutral.”

In opposition to the consolidated plaintiffs’ arguments, the Republican commissioners claim that the enacted redistricting plan for the Commissioners Court is “race-neutral” and adheres to “traditional redistricting criteria.” The defendants aver that the 2021 redistricting plan does not run afoul of Section 2 nor does it intentionally discriminate on the basis of race.

At two separate junctures, the Republican commissioners attempted to stymie legal proceedings pending the Supreme Court’s decision in Allen. The federal judge presiding over the case ultimately rejected both of these requests and ordered litigation to proceed, holding that the defendants’ entreaties were both presumptuous and dilatory:

[T]he defendants ask this court to speculate that the Supreme Court will alter the standard it announced…for voter-dilution claims under section 2 of the Voting Rights Act…But any delay in reaching a final ruling in this case—and a stay would almost certainly cause such a delay—could impair this court’s ability to issue effective relief…in time for the 2024 election.

Back in April, the judge largely denied the defendants’ motions to dismiss the three lawsuits, thereby allowing litigation to proceed, and in July, the court denied the defendants’ motion for summary judgment. Accordingly, the consolidated plaintiffs’ claims regarding Section 2, racial gerrymandering and intentional discrimination will all be adjudicated at trial.

As a case concerning local redistricting, Petteway could have implications for other local jurisdictions where maps face legal challenges.

As myriad other Section 2 redistricting cases proceed in federal court — many of which challenge city and county-level redistricting schemes — the Petteway case could have a far-reaching effect beyond Galveston County. Sarah Xiyi Chen, an attorney representing the NAACP plaintiffs, told Houston Public Media:

Galveston County is not the only place where people do not have the opportunity to elect the candidate of their choice in their local government…We’re talking about school boards, city councils, county commissioners (affecting) the daily lives of Texans and people all across the country.

In light of the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold Section 2 in Allen, federal courts across the country must continue to assess claims of racial vote dilution in accordance with over four decades of precedent. “It puts a little wind on our backs to have [Allen v.] Milligan affirm 40 years of precedent and particularly for our Section 2 case, because what our clients allege in the Section 2 case is very similar to what the plaintiffs in Alabama allege,” stated Valencia Richardson, an attorney for the Petteway plaintiffs.

The trial in Petteway begins today and is scheduled to run for approximately two and a half weeks. With the primary election for the Galveston County Commissioners Court slated for March 5, 2024, a decision in the case is expected before then.