Felony Disenfranchisement, Explained

In a country that prides itself on democratic values and a government led by “we the people,” as of 2020, there are still 5.2 million Americans who are stripped of their voting rights.

In today’s Explainer, we dive into the laws that disenfranchise millions of Americans on the basis of criminal convictions. We outline the origin of these laws, how they reached today’s scale of exclusion and their unequal impact on people of color.

What is felony disenfranchisement?

Felony disenfranchisement is the denial of voting rights on the basis of a felony conviction. Although laws preventing people with criminal convictions from voting can be traced to colonial times, most modern felony disenfranchisement laws originated in the time period after Reconstruction, when post-Civil War constitutional amendments granted the right to vote to Black men. Southern states promulgated felony disenfranchisement laws at the same time they were devising other tools such as poll taxes, literacy tests and grandfather clauses designed to prevent Black voters from accessing the ballot.

The racist origin of most felony disenfranchisement laws mirrors the expansion of new legal codes that aim to incarcerate African Americans. Since then, mass incarceration and explosive prison and jail population growth — increasing by 700% over the past 50 years — means that 2.3% of the voting-age population in the United States is excluded from political participation.

Felony disenfranchisement laws vary widely across the United States, often creating confusion or misinformation for people who are incarcerated, whether they lose their voting rights or not. Notably, a large share of incarcerated individuals serve time for misdemeanor convictions or are held pre-trial — meaning they have not yet been convicted of a crime. These people maintain their voting rights, although they often face immense barriers to actually accessing and casting a ballot.

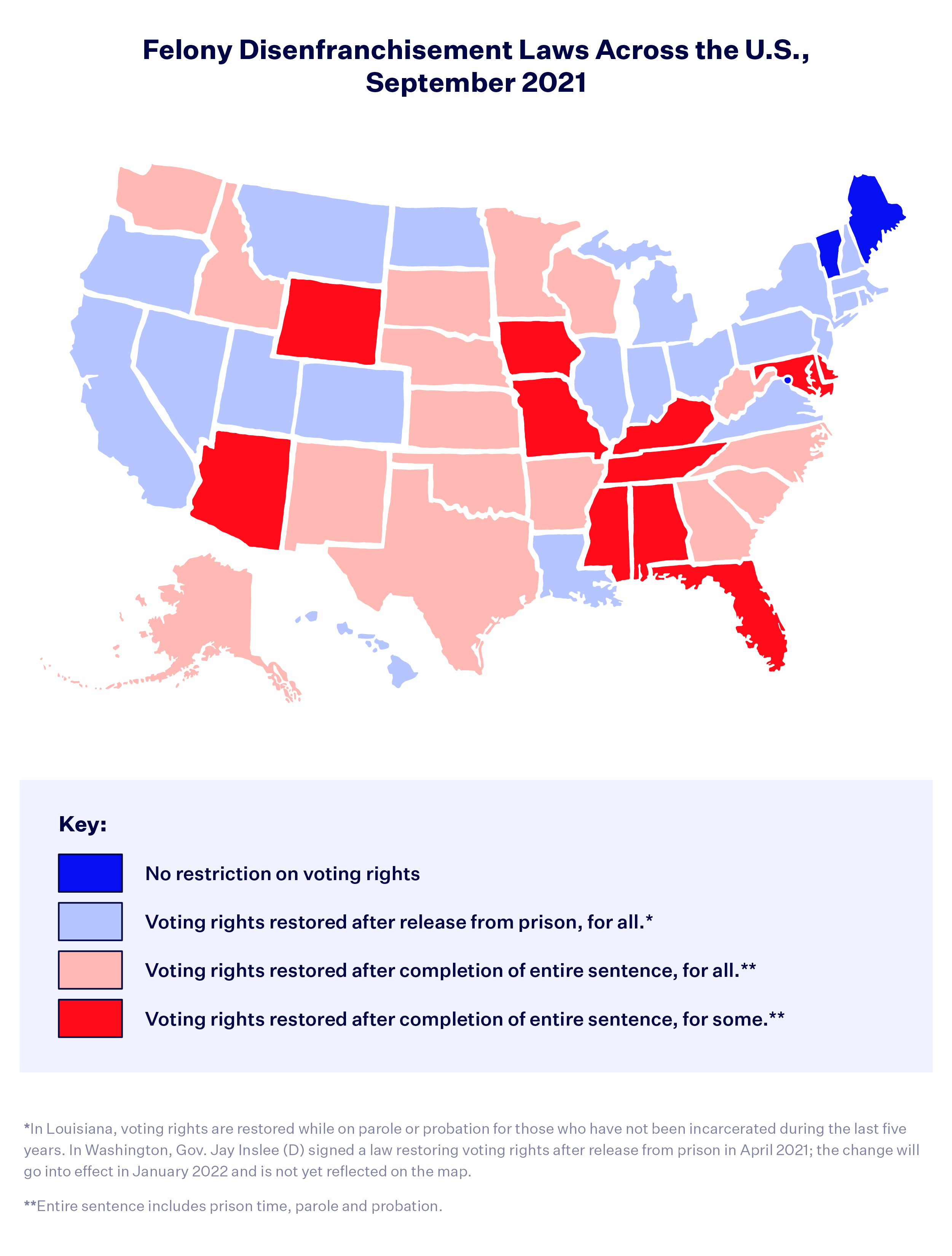

In Maine, Vermont, Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico, all citizens can vote in prison, regardless of their conviction status. In the other 48 states, the laws range from restoring voting rights for all incarcerated individuals automatically after their prison sentence to permanently disenfranchising certain people for life, except if they seek a specific exemption.

How is felony disenfranchisement a racial justice issue?

Because of the racial disparities in policing and sentencing, communities of color are disproportionately denied voting rights. One of every 16 Black adults are disenfranchised nationally. In seven states — Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, Virginia and Wyoming — the disenfranchised population comprises upwards of 15% of Black adults. Although data is more limited, it is estimated that the growing Latino population in the United States is also overrepresented in the criminal legal system. Black, Latino and Native populations are disenfranchised at a rate higher than the general population and their white counterparts in nearly every state.

What’s the status of felony disenfranchisement laws nationwide?

In 2016, there were four states — Florida, Iowa, Kentucky and Virginia — that barred all people who were convicted of felonies from ever voting again, even after the completion of their entire sentences. All four states have since overturned these rules in practice, although disenfranchisement laws remain in most of their state constitutions.

In November 2018, 65% of Florida voters supported Amendment 4, a high-profile ballot initiative to automatically restore voting rights for those with felony convictions, with a few exceptions, after the completion of their sentences. In the past few years, Democratic governors in Kentucky and Virginia have used their executive power to restore voting rights, and a constitutional amendment is also gaining traction in Virginia to officially change the state’s disenfranchisement clause. Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds (R) issued a similar executive order in August 2020.

Considering the recent momentum in this policy area, let’s re-examine the status of felony disenfranchisement laws across the country, as of 2021.

In the 11 most restrictive states, voting rights are never restored for some people.

In 11 states, some citizens are permanently disenfranchised after a felony conviction on the basis of multiple or disqualifying offenses. For example, Florida’s 2018 expansion excludes those convicted of homicide or sexual offenses. Alabama defines crimes of “moral turpitude” and several other states have similar exclusions for certain violent offenses or those related to election crimes.

The categories in the map above do not capture the varying requirements on fines paid or time elapsed before restoration (for example, Nebraska requires a two-year waiting period after completion of sentence). Additionally, some states, such as Wyoming, have a combination of confusing and narrow eligibility requirements. In Wyoming, the only people who regain their voting rights are those who were convicted of a first-time, non-violent felony in or after 2016. Even so, those people must wait five years after the completion of their sentence. In Wyoming or elsewhere, those who are not automatically enfranchised can apply for individual restoration by the governor.

Many states require the completion of an entire sentence — prison time, parole and probation — before restoration, which means people are still excluded from the political process even after they return to their communities.

According to a report by the Sentencing Project, only 25% of the disenfranchised population are currently in prison or jails. Instead, the other 75% of disenfranchised individuals are living in their communities, whether completing parole or probation or having already finished their entire sentence.

Lawmakers haven’t made the process easy for those returning to their communities. In response to the constitutional amendment in Florida, the Republican-controlled Legislature passed a bill to permit voting rights restoration only after all court fees and fines associated with convictions are paid in full. In practice, this law — which has been called a “modern day poll tax” — disenfranchises otherwise eligible voters on the basis that they cannot afford these financial obligations. The New York Times recently reported on Floridians who face outstanding debts that range from a few hundred to several tens of thousands of dollars, effectively a lifetime bar on voting for those struggling to regain their footing after incarceration.

In 20 states, voting rights are restored automatically after individuals are released from prison.

In 20 states (plus Maryland, for almost all convictions except election crimes, and Washington starting January 2022), when an individual leaves prison, they regain their voting rights.

While indicating a causal relationship between recidivism and disenfranchisement is methodologically challenging, several studies have nonetheless considered how the loss of voting rights impacts the rate of repeat offenses. Anecdotally — and intuitively — there is a link between regaining a fundamental, shared right immediately after release from prison (rather than months or years later) and feeling a sense of inclusion and civic duty that contributes to successful reintegration.

In two states, plus Washington, D.C., anyone can vote in prison, regardless of their conviction status.

Maine and Vermont have universal voting enshrined in their constitutions, but what does it look like in practice? There are still numerous logistical challenges for people to vote from prison; barriers include lack of access to ballot applications, information on candidates or simply, Internet access. Departments of correction often rely on outside volunteer groups to facilitate the process of registration and absentee voting, but neither Maine nor Vermont collects significant data on political participation behind bars. Notably, these New England states have the two of the lowest incarceration rates across the country.

In July 2020, the Washington, D.C. city council passed a police reform bill with a provision extending the right to vote to any resident imprisoned for a felony conviction, making Washington the first to proactively restore voting rights in prison. Proposals for similar reforms are increasingly common in places such as Massachusetts and Hawaii, with activists and lawmakers across the country hoping to move towards actualizing the ideal of universal suffrage.

In September, Senate Democrats introduced The Freedom to Vote Act, S.2747, a compromise voting rights bill that includes a provision to restore voting rights automatically after release from prison. Initially included in S.1, The For the People Act, the provision known as The Democracy Restoration Act would ensure that everyone living in their communities has the right to vote and would provide a federal floor to simplify the patchwork of laws currently seen across the country. If The Freedom to Vote Act is passed, the right to vote could not be abridged on the basis of a criminal conviction unless the “individual is serving a felony sentence in a correctional institution or facility at the time of the election.”

As a nationwide focus on voting rights intensifies, the question of felony disenfranchisement challenges our understanding of citizenship, political participation and equal rights. In the meantime, however, millions of Americans remain locked out of the political process.