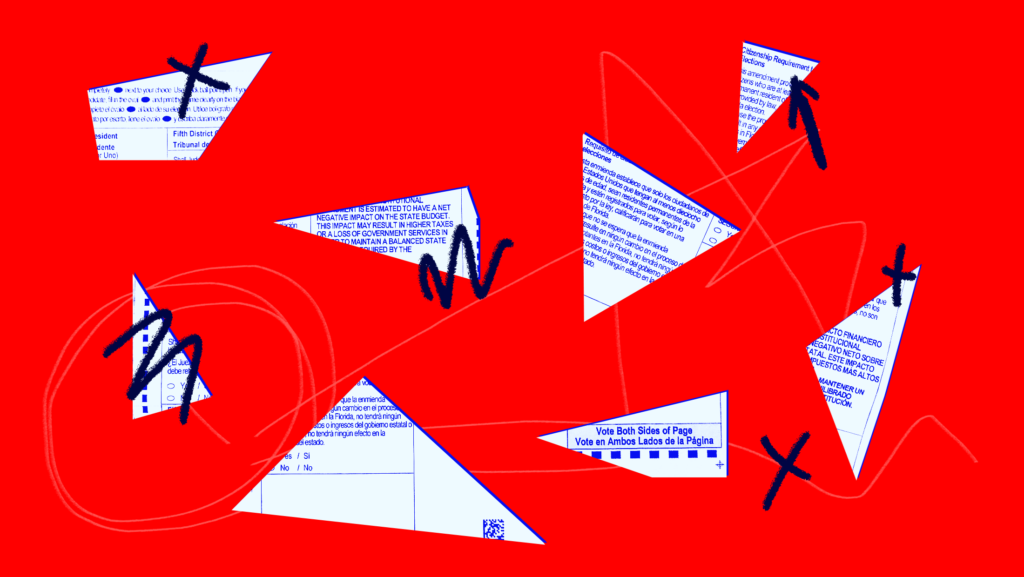

Efforts To Disqualify Thousands of Voters Surge Ahead of Midterms

“In Arizona, we have identified over 55,000 of these voters. In Georgia, 125,000. In Pennsylvania, 142,000,” Matt Braynard, a former staffer from former President Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign, shared with Steve Bannon. Braynard is referring to thousands of registered voters in key swing states that his right-wing organization, Look Ahead America (LAA), plans to challenge. The goal is to kick these voters, which the group deems “ineligible,” off the voter rolls before the November midterm elections.

In 29 states, any private citizen can challenge the eligibility of other prospective voters up to, and sometimes on, Election Day. In a dozen other states, that authority is limited to elections officials or poll watchers. To challenge a voter, an individual must have a suspicion that a registered voter is actually not qualified to vote (by residing in a different county or state, for example). The accusations are often based on erroneous or misinterpreted data. Wrongful, mass challenges — like those proposed by LAA with their network of “local activist groups” — can be discriminatory and disruptive and overwhelm election offices during an already busy time of year.

The National Voter Registration Act (NVRA) prohibits list maintenance programs that remove voters en masse within 90 days of a federal election and outlines other protections against improper voter purges. Nonetheless, this year — even within the 90 day window — attempts to disenfranchise voters are proliferating across the country.

Georgia

Challenges have surged in the Peach State, with upwards of 65,000 so far. In May, the Atlanta-Journal Constitution reported that a man challenged the voter eligibility of 13,000 voters in Forsyth County, Georgia. In this case, a single individual was able to risk the registration status of around 8% of the county’s registered voters. (The county’s election board quickly dismissed the challenge, which came just weeks before the 2022 primary election.)

More recently, there have been 37,500 challenges in Gwinnett County, a populous, diverse county in the Atlanta metropolitan area and 1,350 in Cobb County, another Atlanta suburb. In Cobb, the challenge focused on voters whose registrations were missing apartment or dorm numbers, improperly capturing many college students in the mix. County officials have rejected most of these challenges so far. VoterGA, the group leading some of the efforts, is backed by American Project, a group founded by former Trump National Security Adviser Michael Flynn and former Overstock.com chief executive Patrick Byrne.

This year isn’t the first time there have been mass challenges in Georgia. In the few weeks between the 2020 general election and the January 2021 Georgia runoffs for U.S. Senate, a Texas-based organization challenged the eligibility of over 364,000 Georgians, spurring a still-ongoing voter intimidation lawsuit. Instead of curbing this practice, the Republican-controlled Legislature empowered it with the omnibus voter suppression bill, Senate Bill 202, passed in the spring of 2021. S.B. 202 includes provisions that expressly allow for unlimited, large-scale challenges; the bill statute reads that “[t]here shall not be a limit on the number of persons whose qualifications such elector may challenge.” The law also requires counties to hear challenges within 10 days, no matter how frivolous, and imposes sanctions on boards that fail to comply. Notably, Georgia law does not permit challenges at the polls, an important restriction that was clarified last week.

North Carolina

Other states, however, permit in-person challenges at the polls on Election Day, including North Carolina. A deep dive by WHQR Public Media revealed the work of the North Carolina Election Integrity Team (NCEIT), a citizen-led group that, among other priorities, is looking into how to initiate voter challenges in the state. The director of the NCEIT is creating a “suspicious voters list” of people he believes are double-registered or not citizens. If challenged at the polls, these voters could be forced to instead cast a provisional ballot, which will only be counted if election officials determine the voter’s eligibility. The NCEIT website discusses other methods it may consider using to identify voters to challenge. “The State Board of Elections fact-checked more than a dozen of NCEIT’s claims made on the members-only section of the website, deeming many of them partially or entirely untrue,” writes WHQR authors Laura Lee and Jordan Wilkie.

Yet, there is a 2018 court decision that could stymie NCEIT’s plans. The case arose after the 2016 election when, according to court documents, a “‘handful’ of private individuals brought coordinated and targeted en masse challenges to voter registrations on change-of-residency grounds pursuant to North Carolina’s voter challenge statute.” The lawsuit argued that three North Carolina counties improperly canceled thousands of voter registrations because of these challenges in violation of the NVRA. The district court judge agreed and further prohibited county boards from canceling voter registrations using the challenge procedure without complying with the NVRA’s requirements.

Pennsylvania

Audit The Vote PA, a group founded by “everyday moms who saw what happened in the November 2020 election and knew something wasn’t right,” recently emailed county election officials to ask them to remove voters. According to Philadelphia Inquirer journalist Jonathan Lai, the group asked officials to speak “about a possible remedy to get these electors removed from the voter rolls,” citing more than 242,000 voters the group has identified as no longer living in Pennsylvania. Jonathan Marks, Pennsylvania’s deputy elections secretary, sent clarified guidance to county election officials to ensure they know of the NVRA’s protections against these types of large-scale purges and that the methods used by Audit The Vote are “insufficient by itself for the legal removal of that voter from the voter rolls.”

We can expect these challenges to only increase until the election.

Georgia, North Carolina and Pennsylvania are all on LAA’s list of nine states where it plans to challenge voters. The group is also targeting Arizona, Florida, Nevada, Ohio, Virginia and Wisconsin. Last week, LAA released more information about its research into Arizona voters who submitted National Change of Address requests.

Other challenge examples from this election cycle include:

- Two Nassau County, Florida residents challenged the registration of nearly 2,000 voters less than a week before the August primary election.

- In Iowa, hundreds of registered voters were challenged in two of the state’s most populous counties — a far greater number than in previous election cycles, according to election officials.

- An attempt to challenge over 22,000 voters at once was deemed invalid by the Michigan secretary of state’s office. “State law says challenges must be submitted one at a time rather than in bulk,” the director of the state’s election bureau wrote in a follow up letter to local officials.

- This summer, the election office of Harris County, Texas (home to Houston) received a flood of affidavits challenging around 6,000 voters with the same, formulaic message: “I have personal knowledge that the voters named in this affidavit do not reside at the addresses listed on their voter registration records,” the affidavits read. “I have personally visited the listed addresses. I have personally interviewed persons actually residing at these addresses.” All the affidavits were rejected.

- In Wisconsin, one right-wing activist group is zoned in on a different section of the population — not voters who have potentially moved, but those under a court-ordered guardianship who may have lost the right to vote on the basis of “incompetence.” Wisconsin Watch revealed how the move discriminates against voters with disabilities and conflates court-ordered guardianship with being ineligible to vote.

During the 2022 cycle, these challenges have often been part of a well-funded, coordinated network of groups with links to Trump and other national Republican institutions. If registrations are canceled en masse, that could violate federal law, but nothing has managed to stop these voter fraud vigilantes yet.