Amid Legal Battles, Nevada and Arizona Counties Turn To Hand Counting

In late June, a group of local officials and election workers gathered in a courthouse in Goldfield, Nevada, a small town located in the vast desert between Las Vegas and Reno. The local leaders in Esmeralda County, Nevada were conducting a hand count of the primary election results, responding to calls to do so from residents. Esmeralda County has a population of less than 750; only 317 votes were cast in the June primary. Yet, it took commissioners over seven hours to complete the count, leaving Esmeralda as the last Nevada county to certify its primary results.

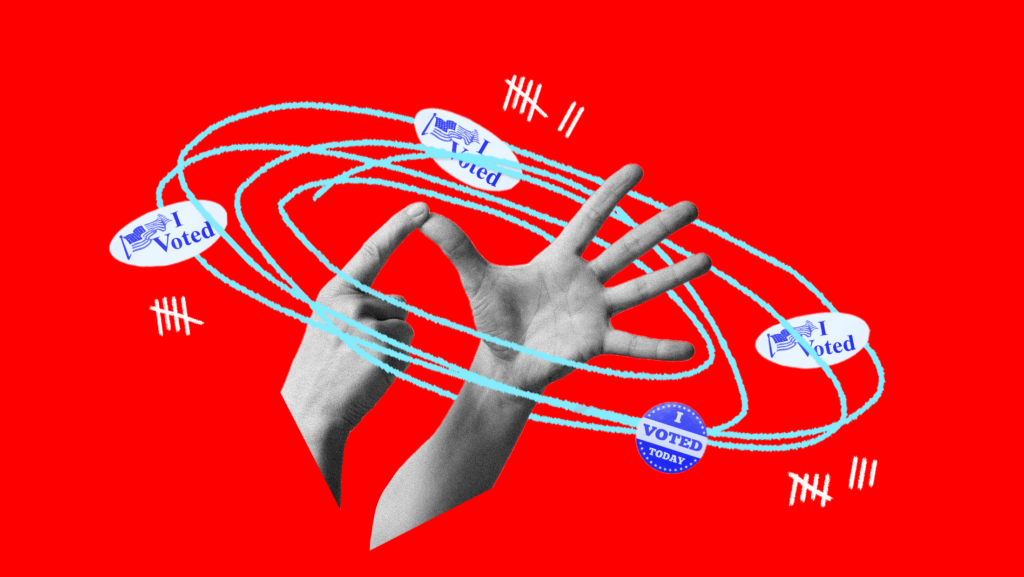

Experts agree that hand counting is less accurate, more expensive and more time consuming than electronic tabulation. Yet, misinformation and conspiracies around voting machines could create major issues after Election Day as more counties — and not just the rural, deep red counties like Esmeralda — implement rogue election procedures. Over the past few weeks, local officials in Nye County, Nevada and Cochise County, Arizona have been at the center of a legal tug of war over moves to push their counties with over 50,000 and 125,000 residents, respectively, to hand count ballots.

The latest jurisdiction that considered a hand count change was Pinal County, Arizona, the state’s third largest county just south of the Phoenix metropolitan area. On Wednesday, Nov. 2, the Pinal County Board of Supervisors held a meeting to discuss potential options for a slightly expanded hand count audit in the county of 450,000. Even with a more measured proposal, the board of supervisors decided to reject this change and stick with the requirements in Arizona law — to conduct electronic tabulation of results, followed by a hand count audit of regular ballots cast, either in two percent of the county’s precincts or in two precincts, whichever is greater.

Hand counting is slower, less secure and less accurate than electronic ballot tabulation.

The New York Times recently spoke with a handful of election administration experts who all concurred: “While hand counting is an important tool for recounts and audits, tallying entire elections by hand in any but the smallest jurisdictions would cause chaos and make results less accurate, not more.” In contrast, electronic ballot tabulators have modernized our elections — making vote counting quicker and more accurate. These types of tabulators are known as optical scan devices; they read paper ballots that were marked by filling in an oval or box shape, similar to the way a machine scores standardized tests. All technology is certified by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission and accuracy testing takes place before elections to ensure the machines are functioning properly.

The Bipartisan Policy Center noted how humans struggle with rote, repetitive tasks, like counting ballots. Electronic ballot tabulators are designed for this purpose. Additionally, the United States has some of the longest ballots in the world because of the extensive list of local, state and federal races. Without electronic tabulators, it would take weeks or months to confirm the results in all the races.

Hand counting ballots can play a legitimate, limited role in the post-election process. A majority of states conduct some type of post-election audit, a routine procedure that verifies the accuracy of the electronic vote count. With traditional post-election audits, a small percentage of paper ballots are hand counted and compared to the results tallied by an electronic voting machine. Risk-limiting audits, a technique that utilizes statistics to decrease the number of ballots audited while increasing confidence in accuracy, are growing in popularity.

Proposed hand counts could create delays and chaos after Election Day.

“I don’t see this continuing,” Esmeralda County Commissioner Ralph Keyes said in an August interview with the Nevada Independent, referring to the county hand counting future election results. Instead, other counties are jumping on board.

In early September, the clerk’s office in much-larger Nye County, Nevada announced a plan to hand count the results of the midterm elections alongside parallel electronic tabulation. (While guidance from the Nevada secretary of state permitted counties to hand count ballots at their discretion, no county submitted a proposal to use hand counting as its sole, primary method.) The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Nevada challenged Nye County’s planned changes to election administration. On Oct. 21, the Nevada Supreme Court held that Nye County is prohibited from live streaming the hand counting process in which election results are read aloud prior to polls closing on Election Day.

Last Wednesday, Oct. 26, a group of volunteers began the count in Nye County, processing 900 of the mail-in ballots that the county had received so far. According to the Associated Press, it took several groups three hours to count 50 ballots each, with mismatched totals forcing multiple recounts. Volunteers appeared exasperated at how time consuming the effort was. The following day, after witnessing Wednesday’s messy procedures, the ACLU asked the Nevada Supreme Court to immediately weigh in on whether the county was violating state law by reading the content of the ballots within hearing distance of poll observers. The state Supreme Court agreed with the ACLU, prompting Nevada Secretary of State Barbara Cegavske (R) to send a letter to the county commissioners, telling them that the “current Nye County hand counting process must cease immediately.”

In response, Mark Kampf, Nye County’s interim election clerk, sent a statement indicating that the county intends to “resume as soon as our plan is in compliance with the Court’s order and approved by the Secretary of State.” Despite Kampf’s insistence that the remaining process will run smoothly, the debacle on the first day of hand counting exemplifies that this old fashioned method is simply less accurate and efficient. If the process resumes, county volunteers and officials will likely encounter more obstacles.

Expanded hand counts efforts are proceeding — similarly with some back and forth over issues of legality and facing a lawsuit — in Cochise County, Arizona, home to over 125,000 residents. In a county of that size, it may be impossible for Cochise County to complete its audit prior to the state’s certification deadline. States cannot certify their state-level results until all jurisdictions have certified and submitted results, meaning a single county — or in the highly decentralized New England states, a single precinct — can derail the certification process.