After a Cascade of Republican States Left ERIC, What Comes Next?

Since the 2020 presidential election, Republicans nationwide have passed restrictive legislation harming voters, predicated on baseless allegations of widespread voter fraud. They have attacked mail-in voting, limited potential funding sources for election administration and pushed for inefficient and less accurate methods of counting ballots all in the name of rooting out voter fraud. In a twist of irony, the one voting system that effectively reduces voter fraud is the Election Registration Information Center (ERIC), which has seen a cascade of departures from Republican states.

Once uncontroversial and little known, ERIC is an organization comprised of both Democratic and Republican states that is used to ensure accurate voter registration rolls. States that opt-in to the coalition submit voter registration and department of motor vehicle licensing data to ERIC, which then produces a handful of maintenance reports. These reports can show voters who have died, moved states, possess duplicate registrations and those who are eligible to vote but have not yet registered. It is then up to the member states to use the provided data to clean up the rolls and reach out to eligible, unregistered voters.

Following the release of a glaringly false article attacking ERIC on the Gateway Pundit, a far-right website, that alleged numerous falsehoods about the coalition, a wave of departures ensued. Louisiana was first, after Secretary of State Kyle Ardoin (R) announced the state’s departure just weeks after the article was published in January 2022. Then Alabama left, followed by Missouri, Florida and West Virginia. By July 2022, nine states, all Republican-controlled, had exited or announced their departure from ERIC.

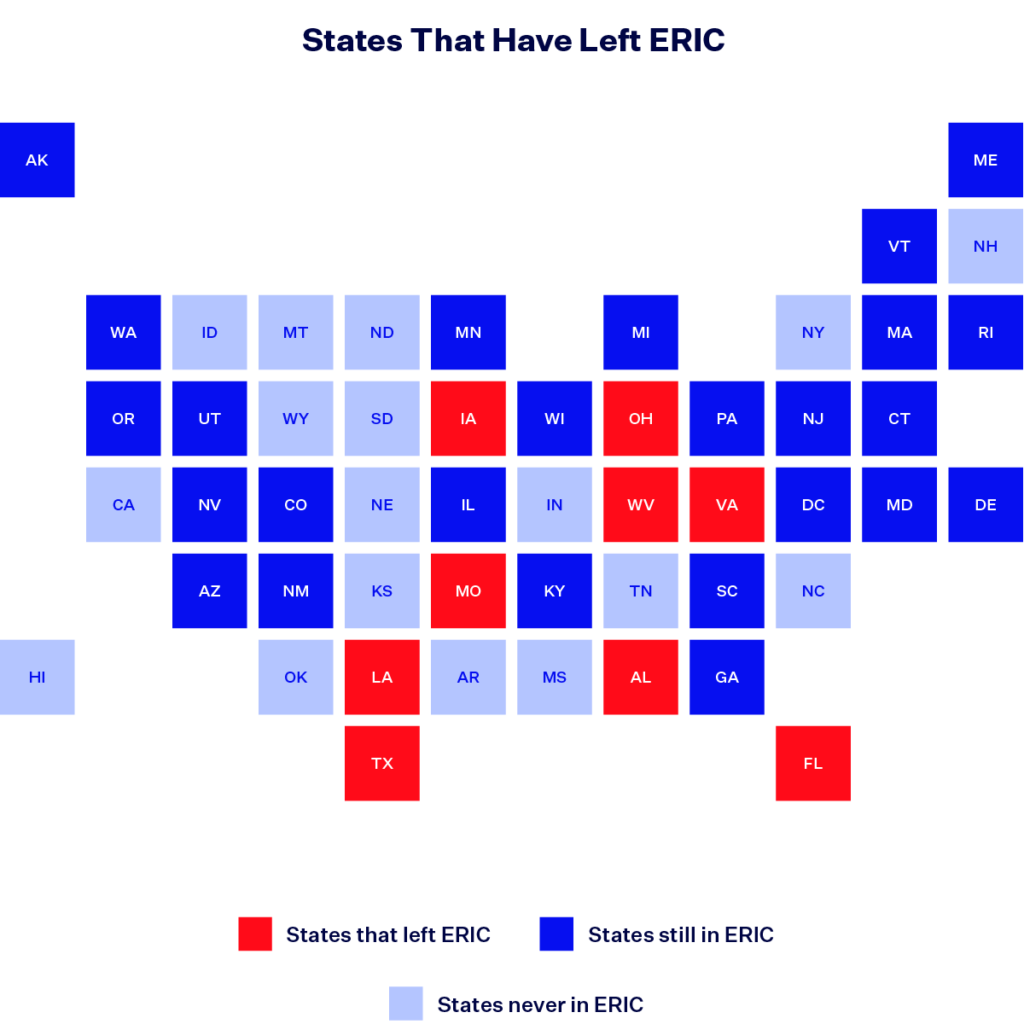

Who’s in and who’s out of ERIC?

The other states that have left the coalition are Iowa, Ohio, Texas and Virginia, and now only five Republican-controlled states remain in ERIC.

Until 2022, membership in ERIC steadily rose in the prior decade, expanding in membership in nine of its first 10 years. Now, less than half of the country is part of ERIC — just 24 states and Washington, D.C. are members — and the group once boasted more than 30.

Additional states are also considering their own departure. In Wisconsin, Republican legislators have proposed a bill that would repeal a 2016 law enshrining the state’s membership and removing Wisconsin from ERIC. Kentucky Secretary of State Michael Adams (R) announced in June that the state would remain in ERIC for another year as it looks for potential alternatives. While Adams claimed that staying in ERIC long term would be “irresponsible” given the coalition’s declining membership, he said it would also be irresponsible to leave at the time, given that no sufficient replacement to ERIC currently exists.

Alaska made a similar decision after considering a departure. The Alaska Division of Elections likewise announced in June that the state would remain in the group “[u]ntil another tool is available that can provide the same or enhanced services.”

After rash decisions to depart ERIC, Republican-led states are scrambling for sufficient replacements.

Unfortunately, not all states had the same thinking as Kentucky and Alaska, and numerous left without seriously considering how they would replace the long-effective organization. Thus far, the best the departed states have been able to accomplish are piecemeal agreements, with less reliable data, that pale in comparison to the abilities of ERIC.

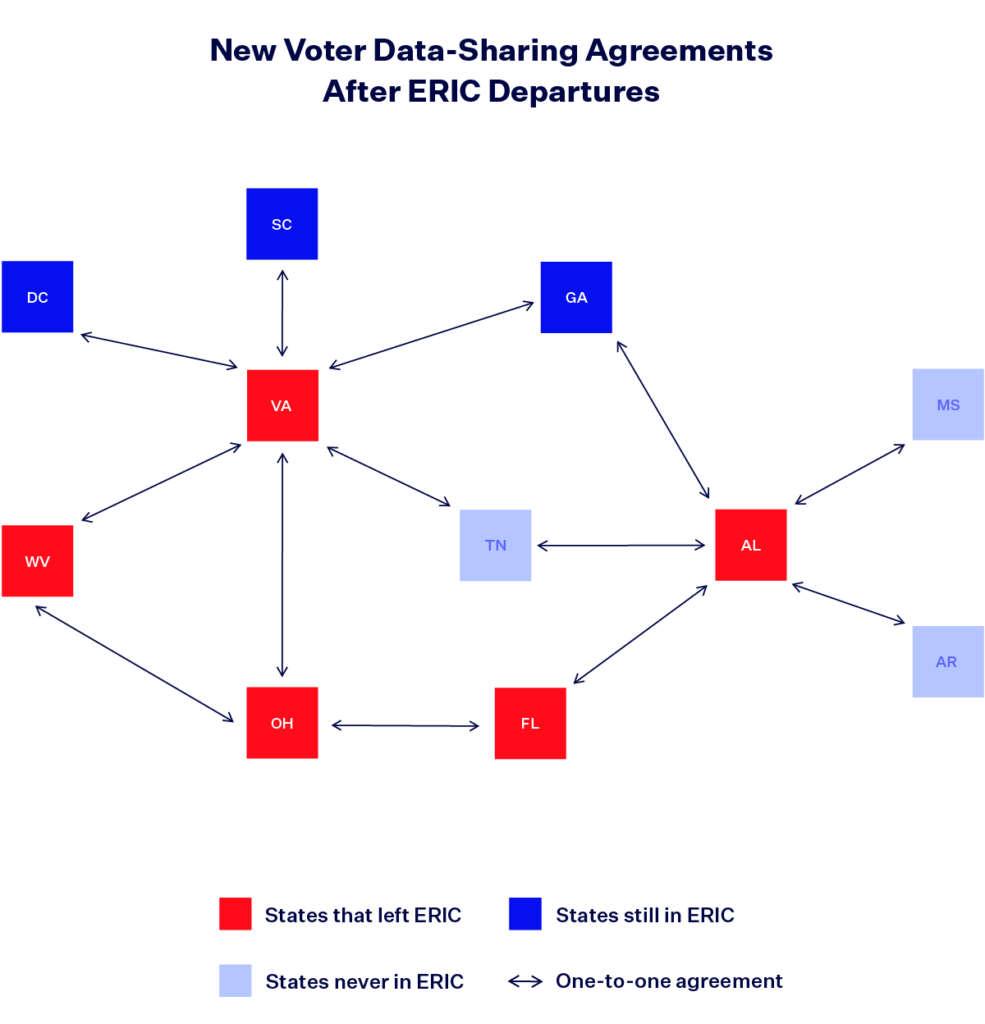

A flurry of recent one-to-one agreements have been made, the largest of which Virginia formed with Georgia, Ohio, South Carolina, Tennessee, West Virginia and Washington, D.C. Ohio also entered into a one-to-one agreement with Florida, West Virginia and Virginia. Alabama has reached data-sharing agreements with every state that borders it, as well as Arkansas. But experts say the Alabama agreements lack detailed security language and it’s unclear how states will actually utilize the data. In all three agreements, Alabama, Ohio and Virginia will share their data with the other states, but the other states won’t necessarily share data with each other.

Alabama is also attempting its own replacement to ERIC, with a system it calls the Alabama Voter Integrity Database (AVID). AVID relies on data such as the U.S. Postal Service’s National Change of Address List, the Social Security Death Index and Alabama’s data to manage its voter list. A similar system called Crosscheck that relied on in-house data was once introduced in Kansas in 2005, but resulted in lawsuits and its eventual abandonment after it was shown to often be inaccurate.

Michael Morse, an election law professor at the University of Pennsylvania who recently published a paper on ERIC, told Democracy Docket that “the Republican states who have withdrawn from ERIC are now trying to effectively recreate Crosscheck,” and expects they “will suffer the same problems” that Kansas did.

The fractured agreements and piecemeal strategies could have devastating consequences.

Data sharing agreements work with strength in numbers — the more states who take part, the more data that is shared — resulting in increasingly accurate voter rolls. When states are only receiving records from just a handful of states, the practice becomes ineffective.

Making matters worse, states are not only receiving and sending less data, but the data that is being shared is less reliable and comprehensive than the data shared between ERIC member states. The coalition benefits from confidential, government-provided data that it can use to ensure accurate registrations. The most crucial data point ERIC relies on is driver’s license data, which typically also includes an individual’s Social Security number (SSN). The new agreements don’t include much of this data.

Morse said the lack of department of motor vehicles data in the new agreements is “the red flag,” and that “[s]tate-by-state agreements without driver’s license data are designed to fail.”

Without confidential data like driver’s licenses, states that rely only on voter registration lists run into trouble because they lack unique identifiers. For example, ERIC is able to delineate between a John Smith in Michigan and a John Smith in Ohio because the group has access to confidential data, like SSNs, that can clearly differentiate the two. The new agreements don’t have the same ability.

Even those that have left ERIC and are forging attempted replacements have admitted to struggles. Missouri Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft (R) has conceded that the state faces limitations because it can’t obtain any data from states who remain in ERIC. Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose (R), who once lauded the organization, has similarly admitted that the new partnership involves less data sharing.

The new agreements also inconveniently leave out an often underlooked aspect of ERIC: its voter registration efforts. ERIC notifies states of voters who have moved, but have not yet registered to vote in their new jurisdiction.

Election vigilantes are exploiting the departures.

Departures from ERIC, and the subsequent need for replacements, have also opened a wide door to dangerous election vigilantism from members of the public. Morse describes voter registration lists as the “vulnerable backbone of election administration,” and seeing the recently created void, activist groups have begun creating their own methods for maintaining voter lists, which could be even more dangerous than the recently announced partnerships.

The most notable endeavor is EagleAI and its software, EagleAI NETwork. Founded by a former doctor with no election administration experience, the program is run not by government officials, but by citizen activists. The group utilizes unreliable public data, and additionally interacts with the Voter Reference Foundation (VoteRef), a Republican group that publishes voter information, including addresses, birthdates, party affiliation and more.

EagleAI’s computer program, self-described as “excel on steroids,” automatically flags registrations thought to be suspicious, which are then evaluated by the vigilantes who can submit them to be challenged. EagleAI has the capability to challenge thousands of voters’ eligibility, predicated on weak information, with just a few clicks.

EagleAI is heavily associated with Cleta Mitchell, an election denier and one-time lawyer to former President Donald Trump. Mitchell and her Election Integrity Network (EIN) have been teaching the program to activists throughout the U.S., and individuals affiliated with EIN have met with elected officials to push the program.

Another company, Fractal, is also seeking to take advantage of the ERIC departures. Though not much is known about the company, it was founded by Jay Valentine, who works for the Gateway Pundit.

Valentine claimed in a pitch email to Texas Secretary of State Jane Nelson (R) that his program manages 1.7 billion voter records, and he once admitted to receiving funding from My Pillow CEO Mike Lindell, a Trump ally and prominent election denier.

Instances of election vigilantism have surged in recent years. Just this month, Virginia Attorney General Jason Miyares (R) warned a right-wing project to “immediately cease and desist” sending false and misleading information to Virginia voters and a group of conservative activists went door-to-door to challenge voter registrations in Washington.

Last month, the New York State Board of Elections similarly cautioned New Yorkers that individuals across the state have been impersonating county board of elections staff, prompting the New York attorney general’s office to send a cease-and-desist to a group accused of confronting voters and falsely accusing people of committing voter fraud.

After succumbing to dangerous and baseless conspiracy theories, Republicans in numerous states are once again threatening election administration. By failing to create sufficient replacements to ERIC, a glaring void has developed — one that is being exploited by bad actors making matters worse.