60 Years Later, Alabama Lawmakers Defy the U.S. Supreme Court Again

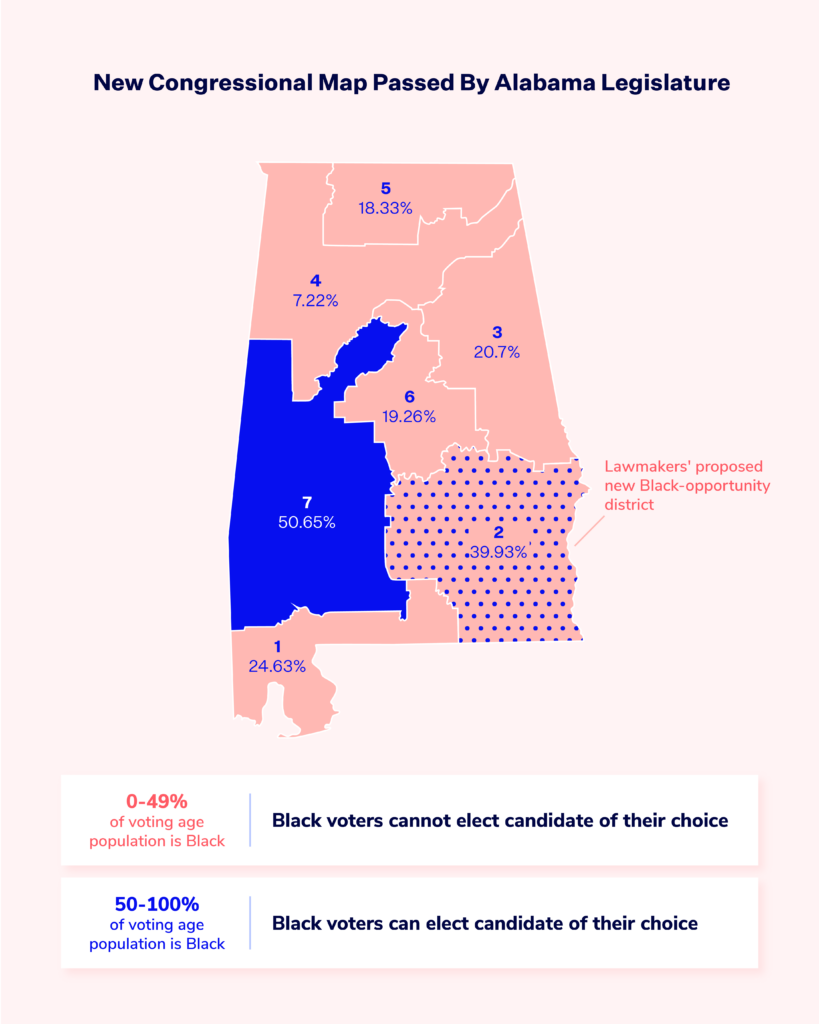

At the end of July, Republican lawmakers in Alabama passed a new congressional map following the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Allen v. Milligan which upheld Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) and affirmed that the state needed a map with two majority-Black districts. However, in direct defiance of federal courts, the new map passed by the Republican-controlled Legislature has only one majority-Black district.

When Gov. Kay Ivey (R) signed the noncompliant maps into law and openly defied the directive issued by the U.S. Supreme Court, she stated, “the Legislature knows our state, our people and our districts better than the federal courts or activist groups, and I am pleased that they answered the call, remained focused and produced new districts ahead of the court deadline.”

This is not the first time that Alabama legislators have defied U.S. Supreme Court decisions in order to weaken the constitutional rights of their Black residents. Beginning in 1954, Alabama waged a decade-long stand-off with the nation’s highest court over desegregation in the public school system following the Supreme Court’s decisions in Brown v. Board of Education.

“The South will not abide by nor obey this legislative decision by a political body.”

In 1954, in Brown v. Board of Education (1) the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously decided that racial segregation in public education violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

However, the Court’s decision to overturn the “separate but equal” doctrine was not enthusiastically heeded by states, prompting the Court to hear Brown v. Board of Education (2) to decide how to implement the principles announced in Brown 1. This time the Court ruled that states must fully comply with “all deliberate speed.” Given the controversial nature of the decision, however, the Court did not provide a firm timeline.

In the months that followed, full compliance varied from state to state, including some states that outright refused to comply with the decision. In fact, white, Southern politicians gathered after Chief Justice Earl Warren finished reading the Supreme Court’s unanimous opinion in Brown 1 and vowed to defy the Court with a plan of concerted “massive resistance.”

In Alabama, the state Board of Education voted unanimously to continue enforcing segregation in the public school system in the weeks following Brown 1.

On the day of the Board’s vote in 1954, Gov. Seth Gordon Persons (D-Ala.) introduced the resolution that extended racial segregation “until the state educational system is directly involved in a racial suit.” In 1963, the newly inaugurated Gov. George Wallace (D-Ala.) declared, “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” But over the course of a week in September 1963, four Huntsville public schools technically integrated with the enrollment of four Black students. In 1966, the Alabama Senate then passed a law that forbade public school desegregation. In 1969, the U.S. Supreme Court stepped in to demand that Alabama immediately integrate its schools, but was met with mixed success.

In fact, Sumter County, located in the Black Belt, did not open its first desegregated school almost 65 years after Brown 1. A recent study found that public schools in Alabama’s Black Belt are more segregated now than they were in 1990.

This past June, two U.S. Supreme Court decisions ended affirmative action in higher education, a policy meant to address inequalities, including those wrought by segregation. In her dissent for the University of North Carolina affirmative action case, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson argued: “Gulf-sized race-based gaps exist with respect to the health, wealth, and well-being of American citizens. They were created in the distant past, but have indisputably been passed down to the present day through the generations.”

Those race-based gaps still exist within the Alabama public school system. The zip codes that determine where people live, what school they go to and what district they vote in are the consequences of generations of segregation and discrimination. With maps that dilute the voting power of Black residents, many communities’ ability to advocate for their needs is greatly hindered.

“The Legislature knows our state, our people and our districts better than the federal courts.”

Just as in 1954 when Alabama’s legislators proceeded “as though nothing had happened” following a directive from the U.S. Supreme Court, those interested in maintaining white political power in the southern state have once again ignored the Court.

When the U.S. Supreme Court decided Allen at the beginning of June 2023, it affirmed a district court decision that struck down the state’s original congressional map for likely violating Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). The Court thus affirmed that Alabama must redraw its map to include a second majority-Black congressional district.

By passing a noncompliant map, one that includes only one majority-Black district, the Republican-controlled Legislature blatantly ignored that ruling. Despite the plaintiffs providing a plan to the Legislature that complies with the VRA and includes two majority-Black districts, Alabama Republicans advanced their own plans that contain only one.

This new map has a 39.93% Black voting-age population in the state’s 2nd Congressional District and 50.65% in the 7th Congressional District. The map clearly lacks a second district that would allow Black voters to have the opportunity to elect the candidate of their choice, plainly violating the district court’s 2022 order, which stated that “any remedial plan will need to include two districts in which Black voters either comprise a voting-age majority or something quite close to it.”

This current fight between lawmakers and their constituents has reminded people of the fight for desegregation in Alabama. Former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder (D), who leads the plaintiffs in Allen, responded to the map’s enactment: “[T]heir goal was a map that prioritized their state partisan needs and national political objectives. The result is a shameful display that would have made George Wallace—another Alabama governor who defied the courts—proud.” The same Wallace who declared, “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever,” some 60 years ago.

“The Alabama Legislature believes it is above the law. What we are dealing with is a group of lawmakers who are blatantly disregarding not just the Voting Rights Act, but a decision from the U.S. Supreme Court and a court order from the three-judge district court.”

Alabama was one of the states covered under the Voting Rights Act’s preclearance requirement, an enforcement mechanism that prevented discrimination against Black voters. In 2013, in the Shelby County v. Holder opinion that ended preclearance, Chief Justice John Roberts justified the opinion by writing, “our country has changed.”

Once again, however, Black people in Alabama are wrestling for fair access and representation from their lawmakers.

As state Rep. Prince Chestnut (D-Selma), explained after one of the map votes last month, “Once again, the state supermajority decided that the voting rights of Black people are nothing that this state is bound to respect, and it’s offensive, it’s wrong.” The defiance along party-lines, he added, “shows Alabama still has the same recalcitrant and obstreperous mind-set that it had 100 years ago.”