The Republican Party’s Voter Fraud Vigilantes

On July 22, a federal judge ruled in favor of the Voter Reference Foundation (VoteRef), a conservative group that wants to publish the information of New Mexico’s voters on a public database. Back in March, the New Mexico secretary of state referred the organization to the state attorney general for possible prosecution, spurring the current lawsuit and VoteRef’s win in court. A few days ago, the organization threatened to sue Virginia over its state laws that protect voter information.

An online database with semi-public voter information in itself may not sound harmful, but coupled with VoteRef’s claims of voter fraud, this represents just another step in the growing, right-wing movement to deputize the task of investigating elections to private citizens.

VoteRef is operating in a gray zone of legality in some states and advancing a “Big Lie” agenda.

VoteRef currently has 31 states and Washington, D.C. on its database, an ever-changing number depending on the organization’s legal battles with state officials. The free, user-friendly platform contains names, addresses, birthdates, party affiliation and voting histories. State laws governing the access to and use of voter registration lists vary from state to state. Numerous states allow any individual to request the list as long as they pay a fee while others limit list access to political parties or other entities involved in campaigns and get-out-the-vote efforts. Additionally, victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, stalking and other crimes are protected by the Address Confidentiality Program in 43 states, a service that keeps sensitive information off of public records.

VoteRef, a well-funded effort backed by billionaire donor to former President Donald Trump, Richard Uihlein, is placing this information online with a clear objective: to reveal “discrepancies” in the 2020 election. VoteRef compares the ballots cast in the 2020 presidential election with the number of voters on voter registration lists. “Theoretically, these numbers should match,” writes the organization, despite the fact that election officials and state governments have reiterated that there are many reasons for these numbers not to match.

For example, Virginia’s strict voter information laws are in place to prevent this type of misanalysis. The state wants to ensure “that accurate information is posted online, as opposed to outdated voter rolls, which are only accurate the day they are pulled from the voter registration system,” said a spokesperson for Gov. Glenn Youngkin (R) after Virginia’s recent spat with VoteRef. “In Virginia, voter lists are updated each and every day to account for people moving or passing away.” ProPublica contacted Democratic and Republican election officials in 12 states who all agreed that VoteRef uses incomplete data or incorrect calculations.

Beyond VoteRef’s own analysis, the organization is encouraging private citizens to scrutinize the data for irregularities. “Citizens will be able to check their voting status, voting history, and those of their neighbors, friends, and others. They will be able to ‘crowd-source’ any errors,” VoteRef wrote in one of its first press releases in August 2021.

VoteRef fits into a larger trend: encouraging ordinary people to act as “voter fraud” vigilantes.

A potential spillover effect of VoteRef’s efforts is an increase in voter challenges, a legal, though deeply flawed, practice in many states that allows private citizens to challenge the voter eligibility of other voters. Voter challenges are often based on suspicions that a voter has moved or is ineligible for another reason; VoteRef makes it easier to source data for nefarious, mass challenges. In Georgia, this year so far, over 25,500 people have had their voter registration challenged and over 1,800 have been removed from the voter rolls.

In March, a group of residents in Otero County, New Mexico — a solid red county that would later be embroiled in a standoff over election certification — knocked on doors with the goal of canvassing the voter rolls. The self-titled New Mexico Audit Force, sometimes falsely presenting themselves as county employees, asked voters to disclose how they voted and who else is present in their household. A similar effort took place in Colorado, where a local volunteer group knocked on nearly 10,000 doors; in addition to questioning voting habits, canvassers were encouraged to carry guns, take pictures of homes and interrogate residents about fraudulent ballots. A group of civil and voting rights organizations sued this Colorado canvasser group for violating the Voting Rights Act and Ku Klux Klan Act, both of which prohibit voter intimidation. The neighborhood canvassing method is equally present in Tarrant County, Texas and proliferating across the country.

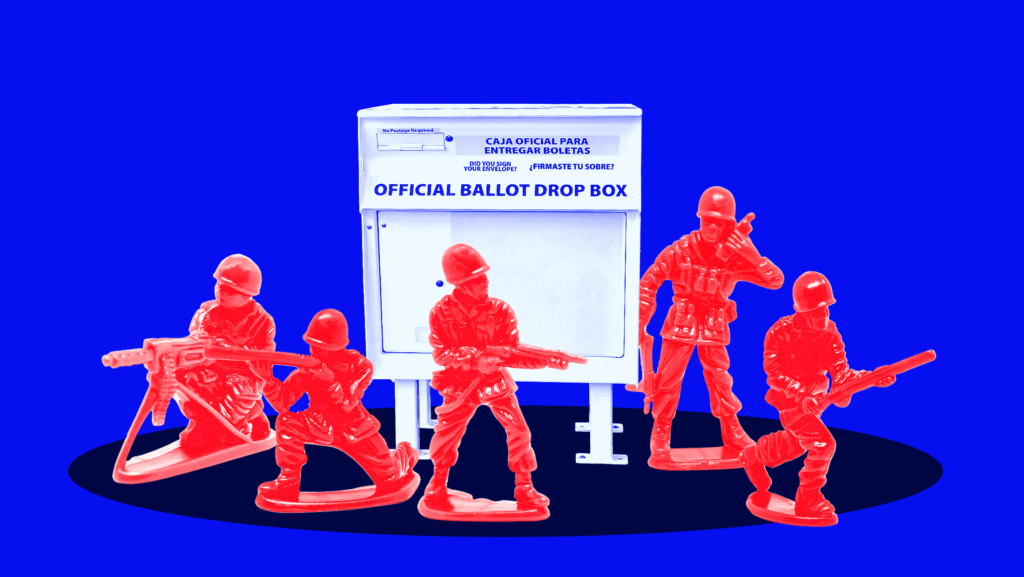

In Arizona, vigilantes were called upon to monitor ballot drop boxes, which have become the target of conspiracy theories. A state senator encouraged these dropbox observers to use cameras and keep track of license plate numbers. Across the country, former military and law enforcement members are being recruited to sniff out fraud; police or police-like forces have a deep and troubling history of election intimidation and civil rights groups are sounding the alarm.

From tacit support to outward endorsement, the Republican establishment has fostered this dangerous movement.

GOP institutions — from the Republican National Committee (RNC) to state and local parties and other affiliates — haven’t shied away from these extrajudicial efforts. Days after the 2020 election, Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick (R) offered a $25,000 reward to tipsters who uncovered credible voter fraud evidence, placing a literal bounty on voters. In Florida, the newly created Office of Election Crimes and Security will staff a voter fraud hotline. And, the loudest voice in calling for Arizona’s drop box vigilantes? Mark Finchem, the new GOP nominee for Arizona secretary of state. “The mere fact that you are there watching scares the hell out of them,” Finchem said in a call for supporters to stake out polling locations.

While the RNC has insisted publicly that its focus is simply to ensure that there are trained poll workers to protect the electoral process, Politico recently reported that the RNC is working closely with advocates who are spreading false claims and stolen-election theories. A GOP network of donors, lawyers, party officials and now individual volunteers are recruiting and training an “army” of poll workers and poll watchers.

States already abide by federal law to maintain accurate voter rolls. But now, “do it yourself” investigators are using VoteRef’s inaccurate data and traipsing door-to-door to check voter rolls. Though exceedingly rare, when election crimes are committed, the perpetrators are often caught and charged by state agencies. Now, untrained citizens are self-appointing themselves as investigators, dead set on unearthing a phenomenon that simply does not exist.

Consequently, this election year, the possibilities for voter intimidation, harassment and election chaos are high. It’s all thanks to Trump and other Republican leaders who continue to feed lies to the American people. Millions of people deeply and genuinely believe these falsehoods, and even worse, will act on them, doing the dirty work for the GOP.