Voter Testimony: Louisiana’s Decades-Long Resistance to Black Political Power

After the release of 2020 census data, all states underwent redistricting, reconfiguring political lines to reflect population changes. In Louisiana, the 2021 map-drawing process was controlled by the Republican Legislature, which overrode a veto from Gov. John Bel Edwards (D) to pass a congressional map that maintains the (unfair) status quo.

Black residents of Louisiana compose over 33% of the total population and 31% of the voting age population but, under the enacted map, can only elect the candidate of their choice in a single majority-minority district that snakes between New Orleans and Baton Rouge. It’s one of the Bayou State’s six congressional districts.

Consequently, a group of voters and civil rights organizations sued, arguing that the adopted congressional map dilutes the voting strength of Black voters in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). The plaintiffs in the cases, Robinson v. Ardoin and Galmon v. Ardoin, were granted a preliminary injunction on June 6, meaning that the map was found to likely violate the VRA and was blocked from being used in the 2022 elections taking place in November. The case was immediately appealed to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which allowed this injunction to remain in place. Instead of redrawing a fair map as ordered, Louisiana Republicans filed an emergency application in the U.S. Supreme Court asking it to step in and reinstate the map. On June 28, the Court did just that.

In a tragedy for democracy, Louisiana will hold its 2022 elections under a map that a lower court ruled likely violates the VRA. This case took a circuitous route through three different levels of the federal court system, but today we are rewinding back to the preliminary injunction hearing held in the district court mid-May. In the second piece in our Voter Testimony series, we examine the transcripts and post-hearing briefs and parse through the statistics and legalese of redistricting lawsuits to understand the very real harm that inadequate representation inflicts on Black communities in Louisiana.

Experts showed that Louisiana’s geography, population and voting patterns satisfy key legal criteria.

Without diving completely into redistricting case law, there’s an important 1986 case, Thornburg v. Gingles, in which the Supreme Court established three criteria for demonstrating a pattern of racial vote dilution: (1) The minority group in question must be “sufficiently large and geographically compact” to constitute a political district; (2) the minority group must be “politically cohesive,” meaning the group generally votes for similar candidates and (3) the majority group must also be “politically cohesive” and vote to defeat the preferred candidates of the minority group.

In the preliminary injunction hearing on the state’s congressional map, both redistricting and political science experts testified how these three criteria are readily satisfied by Louisiana’s particularities:

- Experts submitted six different congressional plans that all contain two majority-Black districts, while complying with other traditional redistricting norms. Bill Cooper, one of the plaintiffs’ experts, pointed out that not only do Black voters compose one-third of the state’s population, but the 2020 census revealed that all of Louisiana’s population gains from the past decade were from nonwhite voters. Additionally, the court concluded that the proposed expert plans appear to be more compact than the enacted map. Currently, the enacted majority-Black 2nd Congressional District “packs” Black voters into a winding district connecting Baton Rouge and New Orleans. Instead, the plaintiffs proposed a second majority-Black district, replacing the current 5th Congressional District, which is anchored geographically around Baton Rouge.

- Experts concluded that Black voters are politically cohesive; in statewide and congressional races, they overwhelmingly support the same candidates. For example, nearly 90% of Black Louisianans supported now-President Joe Biden in 2020. In statewide elections where there was a clear Black candidate of choice, these candidates received upwards of 91% of the Black vote.

- The same experts also showed how white voters vote cohesively as a bloc to defeat the candidates preferred by Black voters. In contrast to Black Louisianans, 82.2% of white Louisiana voters supported former President Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election. In statewide contests, the average level of white voter support for Black-preferred candidates was just 11.7%. When examining the last two congressional elections in the 5th Congressional District, that percentage of support drops below 5%.

Notably, these conclusions about racially polarized voting patterns in the Bayou State were not refuted by the defendants. “In the process of drawing districts, it was clear to me that it is, in fact, relatively easy and relatively obvious that one can [draw a second majority-Black district],” Cooper concluded. “I don’t see how anyone could think otherwise.”

Louisiana’s legacy of racial discrimination can’t be ignored.

In 1898, Louisiana convened a constitutional convention. The goal was explicit: to exclude, by all means possible, newly enfranchised Black men from civic life. At its closing, the president of the convention expressed his approval for the newly adopted constitution, asking his fellow delegates, “Doesn’t it let the white man vote, and doesn’t it stop the negro from voting, and isn’t that what we came here for?”

During Reconstruction, five Black Louisianans were elected to statewide office, but there have been none in the 145 years since then.

In more recent history, and with the passage of the VRA in 1965, the U.S. attorney general has objected to Louisiana’s proposed voting law changes almost 150 times over the course of the last 50 years. When asked during the hearing whether practices to suppress the vote of Black communities was a thing of the past, historian Dr. Robert Blakeslee Gilpin responded that “they are very much the defining characteristics of Louisiana politics past, present and certainly it looks like the future.”

Discrimination and disparity are exacerbated by inadequate representation.

Redistricting is often reduced to a partisan race, but the Louisiana testimony reveals how the damage goes much deeper than which party controls the U.S. House. In a state that consistently ranks the lowest in health, education and other important socioeconomic metrics, the communities that bear the brunt of these disparities are further fractured, disconnected and ignored.

A lifelong resident of St. Landry Parish testified about the educational, economic and social ties between St. Landry Parish and Baton Rouge, and how his home county is systemically overlooked.

When you are cut off from all three [more densely populated areas — Lake Charles, Lafayette and Baton Rouge], you are effectively disenfranchised as far as congressional politics go because nobody cares about you. For instance, right now under the 2011 map, St. Landry is divided between the Northwestern part of the state and the Northeastern part of the state. As far as I know, the congressman from Shreveport has never visited.

Another witness further discussed the ties between areas that would be connected in a map with two majority-Black districts.

The history of that is… Black communities really never leaving the plantation geography of Louisiana.

I know… the importance of congressional representation to bring federal resources home to the district and home to Louisiana and the issues that New Orleans faces and the issues that Baton Rouge face are very different and require their own levels of or their own advocates in Congress to advance those issues.

A business owner and community organizer testified about how the current political lines make it more difficult to advocate for much-needed change.

I’m very active… in my community and also participating widely on Zoom or for policy conferences; and I haven’t seen [my congressman] at any events, whether for King’s Day, Juneteenth Day or just to discuss the plight of the Black community… I have not seen him campaigning during the several elections that I’ve been around for.

In speaking about the organizing she does to improve the lives of her neighboring communities, the voter made an observation, identifying the heart of the issue:

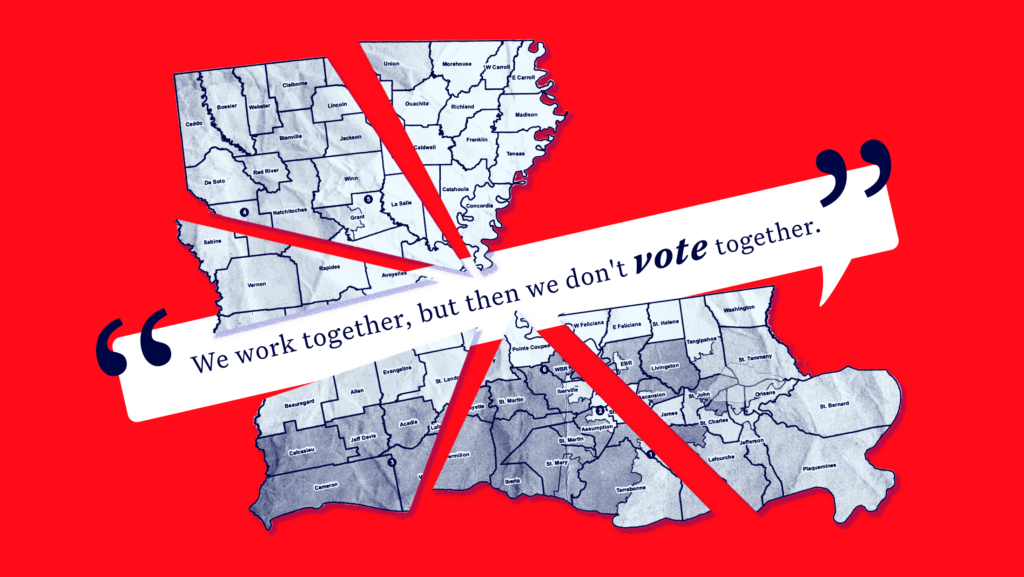

We work together, but then we don’t vote together.

In Louisiana, a lack of representation and the failure of elected officials to be responsive to the needs of the state’s large Black community has continued to perpetuate discrimination and disparity. No example is more illustrative than the highly polluted corridor along the Mississippi River that’s colloquially known as “Cancer Alley.” With petrochemical facilities concentrated in the backyards of predominantly Black and poor neighborhoods, the health impacts have been devastating. The number of industrial plants with toxic releases has dropped nationwide, but the number in this specific region in Louisiana has actually increased in the past few decades.

The Environmental Protection Agency recently opened a series of civil rights investigations into Louisiana state agencies to see if their permitting process has violated the rights of Black citizens. This probe is a result of activism and outrage from the communities that are directly impacted by this startling example of environmental and health racism.

There’s activism and mobilization. But, once again, there’s still inadequate representation.