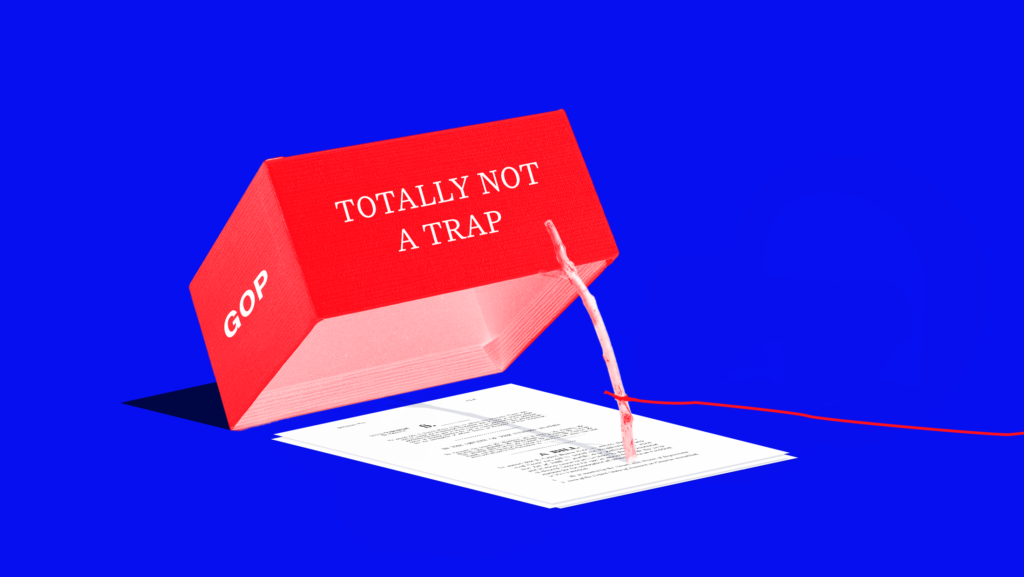

A Trap or Not? Deciphering the Electoral Count Reform Act

Earlier this year, a group of Senate Republicans caught my attention when they claimed that they wanted to work with Democrats to help fix the Electoral Count Act of 1887 (ECA), the outdated law by which presidential elections are certified. The GOP had just finished blocking the Freedom to Vote Act, so at the time, claiming to want to reform the ECA seemed like an effort by Republicans to divert attention from comprehensive voting rights legislation and the devastating findings of the Jan. 6 hearings. On several occasions, I called it a trap.

Nevertheless, when details of the bipartisan bill were released — and nine Republicans cosponsored it — I was intrigued. The proposed legislation, called the Electoral Count Reform and Presidential Transition Improvement Act, was clearly still a work in progress. My concern was that the proposed law might create new vulnerabilities and avenues for election subversion. I offered suggested changes that would make it a bill worthy of passage.

When the U.S. Senate Committee on Rules and Administration announced a hearing to explore the bill in greater detail, I was eager to watch. Yet, despite the testimony of a number of witnesses, I remain concerned about the role of governors in the new proposal and the lack of adequate judicial review of their certification decisions.

This bill gives governors the power to certify election results as “conclusive.”

The new bill provides that a governor’s certification of presidential election results is “conclusive with respect to the determination of electors appointed by the state.” But in a world where full-on election deniers like Kari Lake (R-Ariz.) and Pennsylvania State Sen. Doug Mastriano (R-Pa.) are the Republican nominees for governor, it is a dangerous idea to deem a governor’s certification “conclusive” when determining the outcome of a presidential election.

Such blanket gubernatorial authority is even more dangerous given the bill’s limited judicial review provisions. In addition to a short six-day window for litigation, the legislation makes only a fleeting reference to state court review while providing a detailed process for federal court review. This choice — to prioritize a federal process over a state one — raises the question of whether the bill would, intentionally or not, give election-denying governors the power to falsely certify election results with impunity.

Currently, when a state official refuses to accurately certify election results, a lawsuit is typically filed in state court. Most states have specific statutes that establish certification standards and timelines. If a governor refuses to meet their obligation under state law, they can be sued and the state court can then order the governor to issue a correct certification.

Congress should reinforce the authority of state courts to decide cases regarding federal elections.

In its next term beginning this fall, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear a case called Moore v. Harper, opening up review of the so-called independent state legislature (ISL) theory. Under this theory, which has been advanced by Republicans, state courts could be limited in hearing and deciding cases involving federal elections.

Congress has the authority to protect the rights of state courts to review state laws, but the ECA reform bill fails to take this simple step. In fact, the proposed law altogether ignores this looming threat to state court jurisdiction. Reinforcing the authority of state courts to adjudicate cases regarding federal elections — consistent with centuries of precedent and established practice — is an easy fix to help ward off Republican efforts to oust state courts from the equation.

Instead, the bipartisan bill emphasizes federal court litigation, but again, it fails to close the loop against potential abuse. The bill establishes a process for litigation by presidential candidates — cases are heard on an expedited basis before a three-judge panel. However, the legislation fails to provide any new cause of action for such a lawsuit, meaning an explicit federal right to an accurate election certification. This reading of the law was confirmed by the senators and witnesses who testified at the recent ECA hearing. The result is that the presidential candidates would be entitled to a federal court hearing, but would have no new legal tools to require a rogue governor to correct a false certification.

This distinction is critical because existing legal doctrines instruct federal courts in some instances to abstain from — i.e., stay out of — disputes over election certifications by state officials. In fact, in response to litigation filed by former President Donald Trump after the 2020 presidential election, several states argued that lawsuits challenging election results could not be heard in federal court because of these legal doctrines.

Without a federal cause of action, this bill leaves room for potential abuse by rogue governors.

When it comes to federal court review, the law is unsettled and highly technical. But without a new federal cause of action, there will be disputes about whether a federal court can order a rogue governor to issue a proper certification and even order a governor to take any particular action.

After the 2020 presidential election, Professor Ned Foley, a supporter of the proposed bill, pointed out the problem of federal court review of vote counting and certification. In an article entitled, “Why counting presidential votes is not for federal district courts” he wrote:

[V]ote-counting litigation in a presidential election warrants its own special form of an ‘abstention’ doctrine, or at least yields the conclusion that traditional abstention doctrines as applied to this context calls upon federal district courts to abstain rather than getting involved. But whatever doctrinal label one wishes to attach to this conclusion, these factors combine to provide a strong basis for federal district courts refusing to intervene in the litigation over the counting of presidential ballots.

Whether or not Professor Foley is correct, it is entirely predictable that a conservative federal judge or Supreme Court justice could agree, thus making the newly proposed safeguard against rogue certification a chimera.

To prevent a governor’s rogue certification, Congress could avoid the problem by explicitly providing a federal cause of action under this bill. Yet, during the hearing, several senators and witnesses stated unequivocally that the new law intentionally does not create any such new right or federal cause of action.

This is an odd decision given the state of the law and the conservative bent to the Supreme Court. What makes it more alarming is that, after studying the issue, the American Law Institute — the leading independent legal organization comprised of practitioners, judges and academics — recommended this past April that:

Congress should additionally authorize the federal court to order appropriate injunctive or mandamus relief against the identified State official or body to carry out the federal-law duty to transmit the certificate of identification of electors and their votes. Congress should specify that the provision for injunctive or mandamus relief is severable in case a court deems the granting of such relief to be unconstitutional.

When pressed on this point, some proponents of the new law suggest that Bush v. Gore established a federal cause of action. Ironically, this argument ignores the fact that Bush originated in state court, not federal court. It also ignores the Supreme Court’s warning that it might not consider its opinion precedential in future election cases, writing that the Court’s “consideration is limited to the present circumstances.” Most importantly, that decision did not involve a federal court ordering state officials to certify an election.

All of this brings me back to the question of whether this is all a Republican trap to kill meaningful voting rights reform. At this point I still don’t know, but there is still time to avoid potential loopholes that could end up subverting future elections. If Congress wants a bill worth passing, it needs to solve the problem of election-denying governors who refuse to accurately certify election results. If Republicans won’t agree to that, then perhaps it was a trap all along.