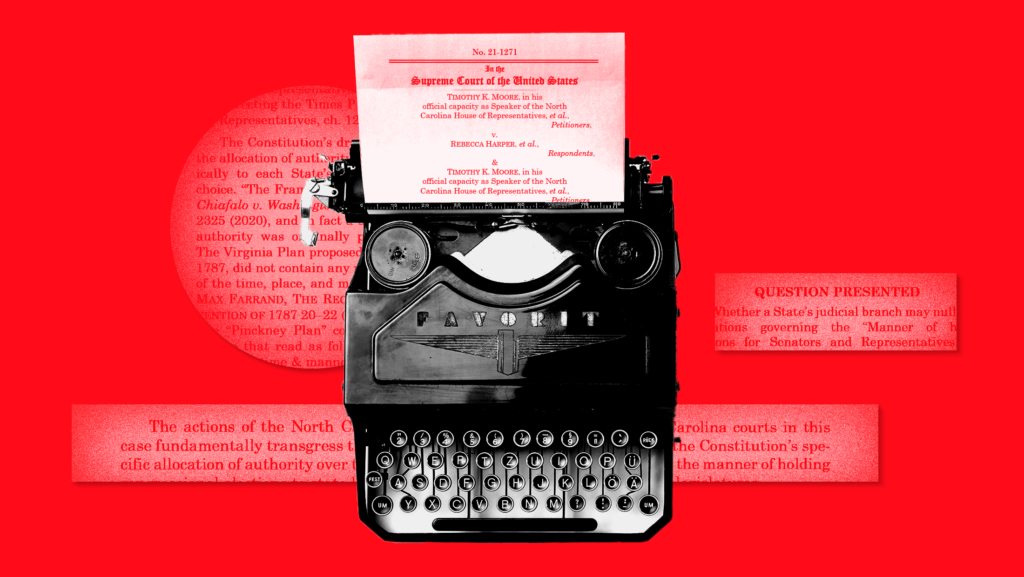

Four Takeaways: Moore v. Harper Oral Argument

On Wednesday, Dec. 7, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral argument in Moore v. Harper, the second major democracy case of the Court’s current term and one that opens review of the fringe independent state legislature (ISL) theory. The dispute centers on redistricting in North Carolina, specifically on whether North Carolina state courts violated the U.S. Constitution’s Elections Clause by striking down the congressional map drawn by the state Legislature and imposing a map drawn by court-appointed experts. According to the ISL theory, the state courts did. How the Supreme Court ends up ruling in this case could have ramifications far beyond the Tar Heel State’s borders. Learn more about how the case ended up before the nation’s highest court and what each side’s arguments are here.

Here are some takeaways from the oral argument.

1. The justices expressed little appetite for the strongest form of ISL theory.

In its strongest form, the ISL theory would give state legislatures sole authority over federal elections, barring restraints imposed by state courts, the governor or even the state constitution. The majority of justices — the Court’s three liberal justices, the chief justice and even some of the other conservatives — appeared to reject this view.

Chief Justice John Roberts asked the Moore lawyer, arguing in favor of the ISL theory, if governors can veto state laws that regulate federal elections. When the lawyer agreed, Roberts pointed out that “the governor is not part of the legislature” and “vesting the power to veto the actions of the legislature significantly undermines the argument that [the legislature] can do whatever it wants.”

Other justices focused on the role of state constitutions in regulating elections. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson asked the Moore lawyer the reason why “what counts as the legislature isn’t a creature of state constitutional law.” Justice Sonia Sotomayor pointed out that “at the founding of the Constitution, decades after, and even to today, state constitutions have regulated time, place, and manner” of federal elections.

Even justices who previously expressed support for some version of the ISL theory pushed back on its strongest claims. Justice Samuel Alito suggested that, even under the Moore lawyer’s argument, it’s inevitable that state courts will have to interpret state election laws in at least some instances. Similarly, Justice Brett Kavanaugh pointed out that the Moore lawyer’s argument “seems to go further than Chief Justice [William] Rehnquist’s [concurrence] in Bush v. Gore, where he seemed to acknowledge that state courts would have a role interpreting state law.” Alito and Kavanuagh, two of the most conservative justices when it comes to voting, were not buying the Moore position.

Only Justice Neil Gorsuch seemed to express unreserved support for the ISL theory, suggesting that the Founding Fathers might have had “concerns…if state constitutions were allowed to trump over state legislatures.” (Gorsuch also spent a significant portion of the argument mired in a colloquy about Virginia’s three-fifths clause.) As a result, a ruling by the Court that endorses the strongest form of the ISL theory — with all its extreme ramifications — seems unlikely.

2. The Moore lawyer attempted to circumvent the Court’s past precedent by drawing flimsy distinctions.

During the course of the argument, the justices frequently pointed out that the Moore position contradicts several past precedents of the Court, including:

- Ohio ex rel. Davis v. Hildebrant (1916), which upheld a citizen’s referendum over a redistricting plan;

- Smiley v. Holm (1932), which upheld a governor’s veto over a redistricting plan;

- Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (2015); which upheld independent redistricting commissions and

- Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), which suggested that state courts could overturn partisan gerrymanders.

Justice Elena Kagan put it simply: “I would think that our precedent gives [the Moore position] a lot of problems.”

The Moore lawyer tried to get around the problems raised by these precedents by attempting to craft distinctions between procedural and substantive constraints on a state legislature, arguing that the prior cases are examples of the former. He contended that what the North Carolina courts did instead counts as a substantive limitation and is therefore unconstitutional without upsetting the prior precedent. Later in the argument, when asked for a narrow ground to decide the case, he tried to draw a distinction between so-called vague constitutional provisions, like North Carolina’s Free Elections Clause, and specific provisions, stating that a specific ban on partisan gerrymandering would pass his distinction and be allowed in accordance with Rucho. As Sotomayor noted, “It seems that every answer you give is to get you what you want.”

The justices were skeptical that these distinctions could be drawn and applied in a meaningful way. Sotomayor outright said that the substantive versus procedural “distinction makes no sense to me.” Roberts asked why a veto qualified as a procedural limitation and Justice Amy Coney Barrett noted that “those are kind of all notoriously difficult lines to draw.” Kavanaugh asked the Moore lawyer where this procedural versus substantive distinction came from. When the Moore lawyer pointed to Rehnquist’s concurrence in Bush, Kavanaugh responded that the concurrence doesn’t use the word “substantive” at all.

The Harper lawyers, who argued against any adoption of the ISL theory, rejected these distinctions. As U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, arguing on behalf of the United States, summarized, that “text, history, precedent, each of those counsels forcefully against drawing this kind of substance/procedure distinction.”

3. The justices seemed to agree a state court could violate the federal Elections Clause.

Over the course of the argument, the justices seemed to reach agreement, in accordance with the Moore lawyer’s contention, that a state court could at some point violate the U.S. Constitution’s Elections Clause and require a federal court to step in to correct the violation. The question then centered on where to draw the line.

Rather than adopting the Moore lawyer’s procedural versus substantive distinction, several of the justices pointed to Rehnquist’s concurrence in Bush as a starting place for determining where this line is. As Kavanaugh put it, that concurrence suggests that federal courts should defer to state courts unless the state court “significantly departed from state law,” only then could there be an Election Clause violation.

Notably, the Harper lawyers didn’t dispute the idea that a federal court can review a state court’s interpretation of state law and the state constitution. Instead, the Harper lawyers argued the standard to determine if a state court departed from state law should be “sky high.” Similarly, the solicitor general acknowledged that there’s a role for federal courts to review state court decisions but that federal courts should be “deferential” because “it is not the ordinary case where the [U.S. Supreme Court] is second-guessing a state court’s interpretation of its own state law.” The solicitor general argued that the appropriate standard for a federal court to step in depends on “the narrow circumstances where the [state court] can’t properly be understood to be conducting judicial review in the first place.” One of the Harper lawyers largely concurred, adding that “the standard is…whether the state decision is such a sharp departure from the state’s ordinary” way of interpreting its constitution and state laws.

If the justices settle on this ground to decide the case, it seems that the North Carolina courts’, specifically the state Supreme Court’s, decisions would be upheld. The Moore lawyer repeatedly affirmed the state Supreme Court’s decision to strike down the Republican-drawn congressional map as “fairly reflecting North Carolina law” and as a result the court did not significantly depart from state law when overturning the congressional map. As Gorsuch stated, “nobody here thinks the North Carolina Supreme Court is exercising a legislative function.”

4. The case will reverberate far beyond North Carolina.

Listening to much of the argument, you could be forgiven for forgetting that this case arose out of North Carolina. The justices spent most of their time discussing hypothetical situations, precedent and history instead of the specific facts in the Tar Heel State.

On one hand, this isn’t too surprising since the Moore lawyer didn’t challenge the North Carolina Supreme Court’s interpretation of the North Carolina Constitution. But the justices also mostly ignored a significant part of the Harper parties’ argument that would have allowed the U.S. Supreme Court to decide the case without reaching the broader ISL theory claims: the fact that the North Carolina Legislature specifically authorized state court review of maps it draws. The justices’ unwillingness to touch on this part of the argument suggests that they intend to make a generally applicable ruling that isn’t just limited to North Carolina.

Indeed, the scope of the justices’ arguments and hypotheticals demonstrate just how broad the ramifications of the case could be. As one of the Harper lawyers noted, the case could “invalidat[e] 50 different state constitutions.” No matter how the justices end up ruling, what started as a dispute over redistricting in North Carolina will likely have an impact far beyond the state’s borders.