It’s Harder for Young People To Vote

There’s little doubt about it: if most young people turned out to vote, Joe Biden would win the 2020 election and Democrats would sweep down-ballot races. Yet 10 weeks before Election Day, it remains unclear whether this youth wave will materialize. In the Democratic primaries earlier this year, youth turnout fell disappointingly short of expectations, contributing to Bernie Sanders’ loss to Joe Biden. And for the general election, only 54% of young adults under 30 say they will definitely vote for president.

Low youth turnout is not a new phenomenon. Consistently, young people vote at far lower rates than older Americans. The contrast is especially stark between youth and senior citizens, who consistently have the highest turnout rates: in 2016, only 46% of eligible young adults between 18 and 29 turned out to vote, whereas close to 71% of people 65 and older voted — a gap of nearly 25 percentage points. Even in the historically high-turnout midterm election of 2018, youth turnout topped out at just 35.6%, compared to 66% for seniors.

Young people have every reason to vote. A bungled government response to COVID-19 is keeping people fearful of infection and socially isolated, student loan debt is skyrocketing, global warming is wreaking havoc on the planet, school shootings threaten college students’ personal safety — the list goes on. They have unique preferences for political candidates (most preferred Sanders to Biden during the primaries) and have different issue priorities: today’s young voters care more about the environment and the treatment of LGBT, Black and Latinx people, whereas older voters care disproportionately about Supreme Court appointments, Social Security, terrorism, foreign policy and trade. Contrary to popular belief, they are also very interested in politics and elections.

Understanding the ways in which young people are especially burdened by the voting process is essential for diagnosing shortcomings of our current voting system — and for identifying the specific policy changes most likely to increase youth turnout in the future.

What explains young people’s consistently low voting rates — especially now, in the midst of the highest-stakes election in living memory? In a new working paper, I argue that youth turnout may be so low because voting is actually harder for young people than for other age groups. In the political science world, we refer to this as voting being more “costly.”

One hint this may be the case: when certain barriers to registration and voting are reduced, turnout jumps disproportionately for young people. A previous study I conducted found that when states let people register to vote on Election Day, rather than making them register well in advance, young people vote at far higher rates. The same goes for all-mail voting: when Colorado began proactively mailing ballots to all registered voters, rather than making people vote at their polling place, turnout went up most for young people.

Yet we know surprisingly little about the ways in which voting might be harder for one age group versus another. This is a clear oversight. Understanding the ways in which young people are especially burdened by the voting process is essential for diagnosing shortcomings of our current voting system — and for identifying the specific policy changes most likely to increase youth turnout in the future.

To explore how voting costs may be unequally distributed across age groups, I conducted a nationally representative survey of more than 2,000 voting-age Americans about their experiences with registering and voting. The survey was sponsored by the Berkeley Institute for Young Americans (BIFYA) and fielded by the polling firm, YouGov, between April 29 and May 13, 2020. (See the working paper for additional methodological information.)

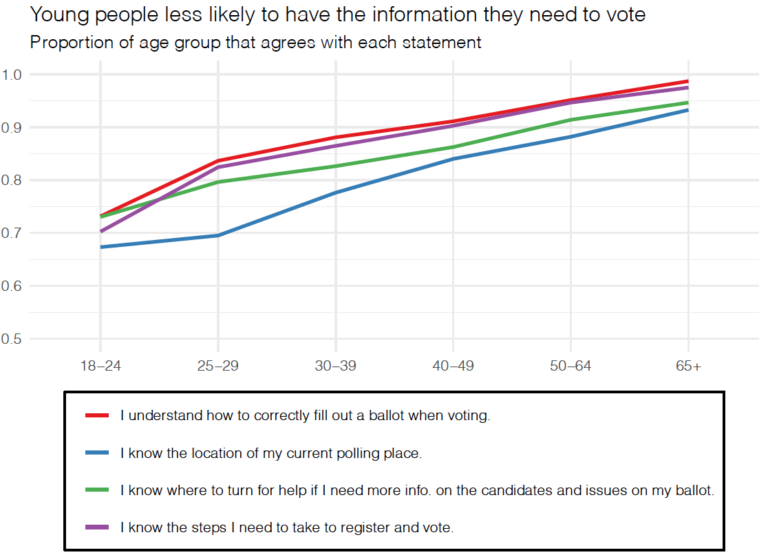

The survey findings were clear: young people face higher barriers to voting than other age groups. They have less information about the voting process and about the candidates and issues on their ballot, less time and flexibility to engage in registration and voting and less ability to balance voting with the other things going on in their lives. They disproportionately face transportation issues when registering and voting and they are more likely to face a tradeoff between participating in elections and earning money. They have a harder time with the parts of registering and voting that cannot be done online, as well as with registering and voting by mail.

Young people are also less likely to have the voter ID documentation they think they need to vote — a particularly concerning finding, given the dramatic increase in strict voter ID laws in recent years.

I also find that, when asked directly, young people are significantly more likely than older Americans to say that registration and voting are difficult. A series of linear regressions finds that, after adjusting for race-ethnicity, gender, education and family income, being young (relative to being a senior) is a large and statistically significant predictor of voting costs. In turn, these voting costs are significant predictors of voting, with information costs the strongest predictors: people who report lacking registration and voting information are up to 57 percentage points less likely to have voted in 2018.

Of course, age is not the only predictor of voting difficulty. Consistently, I find that race and education also have a large bearing on voting costs. People of color and less-educated individuals are more likely to face barriers to voting and to have fewer resources to overcome those barriers. Today’s youth are more racially diverse and have less formal education than older people, further increasing the voting costs for young Americans. However, these differences alone do not fully account for differences in costs across age groups.

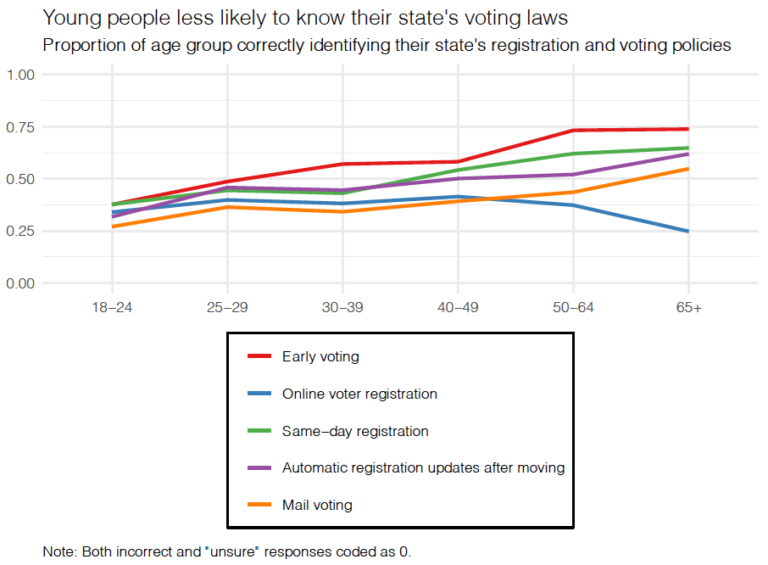

In the vast majority of cases, young people also lack essential information about their state’s voting laws. On average, young people are the least-informed of any age group about their state’s policies on same-day registration, early voting, mail voting and whether individuals must update their voter registration after moving.

Although this finding is surely disheartening for those who see voting reforms as a panacea for boosting turnout, it also has a silver lining. While past scholars have often found that cost-reducing political reforms have only a small effect on turnout, this may be due in good measure to lack of public awareness — not to any inherent flaw or shortcoming of the policies themselves. The implication is clear: political leaders, election administrators and community organizations who want to see higher youth turnout should educate young people about the voting policies where they live.

These survey results drive home that there is no universal voting experience. In many ways, registering and voting are harder for young people than for older adults. It is little surprise, then, that youth tend to turn out at lower rates and have less influence in our political system. To improve the representativeness of America’s elections and political outcomes, it is critical that we acknowledge these inequities within our voting system — and then get to work to fixing them.

Charlotte Hill is a doctoral candidate at UC Berkeley, where she researches election laws and voter turnout, and sits on the boards of nonpartisan election reform organizations FairVote and RepresentUs.